9.8

Pregunta de antecedentes 4

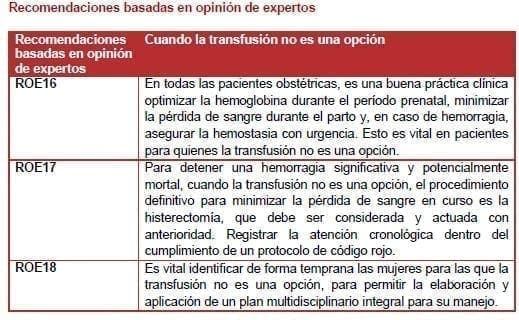

¿Qué orientación se puede proporcionar para ayudar en la atención de las pacientes obstétricas en las que la transfusión no es una opción?

Evidencia

La transfusión de sangre puede no ser una opción de manejo en algunas situaciones (ej. debido a elección personal, creencias religiosas y/o culturales, presencia de grupos sanguíneos poco frecuentes o anticuerpos complejos, o falta de disponibilidad de componentes sanguíneos).

Los estudios observacionales sugieren un mayor riesgo de morbilidad y mortalidad maternas en tales circunstancias, con una atención deficiente (incluida la demora en la toma de decisiones) contribuyendo así a peores desenlaces (115-116).

9.8.1 Atención prenatal

- A principios del período prenatal, identifique las mujeres para las que la provisión de sangre es probable que sea difícil (ej. grupos sanguíneos poco frecuentes).

- Un equipo multidisciplinario debe brindar cuidados obstétricos y asesorar a la mujer sobre el mayor riesgo de morbilidad y mortalidad materna asociado a no recibir una transfusión cuando está indicado. La discusión debe ser individualizada, para determinar los componentes sanguíneos específicos y las alternativas a estos, que sean aceptables para la mujer. Documente el asesoramiento proporcionado y las preferencias de la mujer en el registro de control prenatal y en un formato legalmente válido.

- Identificar y manejar la anemia y la deficiencia de hierro de acuerdo con las pautas establecidas.

- Evaluar a las mujeres con respecto al riesgo de hemorragia, incluidos los factores de riesgo obstétrico establecidos para el sangrado, el uso de anticoagulantes, antecedentes personales de trastornos hemorrágicos hereditarios o adquiridos y antecedentes familiares de trastornos hemorrágicos.

- Asesorar a las mujeres con alto riesgo de hemorragia para dar a luz en un sitio que tenga acceso a procedimientos quirúrgicos, radiología intervencionista y rescate celular si esta es una opción aceptable.

- Prescribir la terapia prenatal de hierro para las mujeres en las que se espera una pérdida de sangre sustancial y que tienen depósitos de hierro subóptimos (ej. ferritina <100 μg/L) (1).

- Considerar los AEE en mujeres seleccionadas con alto riesgo de pérdida importante de sangre. Cuando se utiliza un AEE, debe combinarse con una terapia con hierro.

9.8.2 Manejo en el trabajo de parto

- Informar al servicio de obstetricia y a los especialistas (ginecólogo) cuando la mujer sea admitida en el parto.

- Se aconseja el manejo activo de la tercera etapa del trabajo de parto con oxitócicos.

- Se recomienda la observación cuidadosa y el control de la mujer, incluyendo el registro de la pérdida de sangre y la evaluación fundamental en las primeras horas después del parto, para asegurar la detección temprana y el manejo adecuado del sangrado anormal.

9.8.3 Manejo de la hemorragia

El manejo definitivo temprano puede salvar la vida cuando no se dispone de hemocomponentes para ayudar a optimizar el suministro de oxígeno, el rendimiento cardíaco y la hemostasia.

- Involucrar al personal y activar los protocolos de sangrado postparto con una progresión rápida a la próxima intervención si la hemorragia no se controla rápidamente.

- Considerar el manejo quirúrgico (incluyendo el taponamiento con balón) y radiología intervencionista antes de lo habitual.

- Considerar el rescate celular si está disponible y es aceptable para la mujer.

- De igual manera tambien,, Considerar los agentes farmacológicos, incluidos los agentes hemostáticos tópicos, para ayudar en la hemostasia.

- También, Considerar el crioprecipitado, concentrado de fibrinógeno o concentrado de complejo de protrombina cuando esté disponible y aceptable para la mujer.

9.8.4 Manejo de la anemia postparto

- Use hierro intravenoso en mujeres con anemia postparto moderada, y considere la posibilidad de agregar AEE cuando la anemia sea grave.

- En el caso de la anemia grave postparto, el manejo debe guiarse por un asesoramiento temprano y continuo por parte de un experto.

9.8.5 Aspectos jurídicos y éticos

En cualquier situación en que el rechazo de la transfusión pueda afectar la salud del feto (ej. anemia prenatal materna profunda, transfusión intrauterina), obtenga asesoramiento legal y complete la documentación pertinente, de acuerdo con los requisitos jurídicos.

Referencias

-

1. Koshy M, Burd L, Wallace D, Moawad A and Baron J (1988). Prophylactic red-cell transfusions in pregnant patients with sickle cell disease. A randomized cooperative study. New England Journal of Medicine 319(22):1447–1452.

-

2. National Blood Authority (NBA) (2011). Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 1 – Critical Bleeding/Massive Transfusion. NBA, Canberra, Australia. http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-module-1

-

3. National Blood Authority (NBA) (2012). Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 2 – Perioperative. NBA, Canberra, Australia. http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-module-2

-

4. National Blood Authority (NBA) (2012). Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 3 – Medical. NBA, Canberra, Australia. http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-module-3

-

5. National Blood Authority (NBA) (2013). Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 4 – Critical Care. NBA, Canberra, Australia. http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-module-4

-

6. Hytten F (1985). Blood volume changes in normal pregnancy. Clin Haematol 14(3):601-612. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4075604

-

7. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) (2007). Blood transfusion in obstetrics (2008 revision). Green-top Guideline No. 47, RCOG. http://www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/blood-transfusions-obstetrics-green-top-47

-

8. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RANZCOG) (2003). Placenta Accreta (2014 revisión), RANZCOG. http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/college-statements-guidelines.html

-

9. Titaley CR and Dibley MJ (2012). Antenatal iron/folic acid supplements, but not postnatal care, prevents neonatal deaths in Indonesia: analysis of Indonesia Demographic and Health Surveys 2002/2003-2007 (a retrospective cohort study). BMJ Open 2(6). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23117564

-

10. McCaw-Binns A, Greenwood R, Ashley D and Golding J (1994). Antenatal and perinatal care in Jamaica: do they reduce perinatal death rates? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 8 Suppl 1:86-97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8072904

-

11. Westad S, Backe B, Salvesen KA, Nakling J, Okland I, Borthen I, et al. (2008). A 12-week randomised study comparing intravenous iron sucrose versus oral ferrous sulphate for treatment of postpartum anemia. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 87(9):916–923. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016340802317802

-

12. Hemminki E and Rimpela U (1991). Iron supplementation, maternal packed cell volume, and fetal growth. Archives of Disease in Childhood 66:422–425.

-

13. Pena-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM, Dowswell T and Viteri FE (2012). Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 12:CD004736.

-

14. Pena-Rosas JP, De-Regil LM, Dowswell T and Viteri FE (2012). Intermittent oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7:CD009997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22786531

-

15. Puolakka J, Janne O, Pakarinen A, Jarvinen P and Vihko R (1980). Serum ferritin as a measure of iron stores during and after normal pregnancy with and without iron supplements. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 95:43-51.

-

16. Reveiz L, Gyte GM, Cuervo LG and Casasbuenas A (2011). Treatments for iron-deficiency anaemia in pregnancy. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (10):CD003094.

-

17. Breymann C, Gliga F, Bejenariu C and Strizhova N (2008). Comparative efficacy and safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose in the treatment of postpartum iron deficiency anemia. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 101(1):67–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.10.009

-

18. Gupta A, Manaktala U and Rathore AM (2013). A randomised controlled trial to compare intravenous iron sucrose and oral iron in treatment of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion 30(2):120-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12288-012-0224-1

-

19. Van Wyck DB, Martens MG, Seid MH, Baker JB and Mangione A (2007). Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose compared with oral iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology 110(2 I):267–278. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17666600

-

20. Neeru S, Nair NS and Rai L (2012). Iron sucrose versus oral iron therapy in pregnancy anemia. Indian J Community Med 37:214–218.

-

21. Bencaiova G, von Mandach U and Zimmermann R (2009). Iron prophylaxis in pregnancy: Intravenous route versus oral route. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 144(2):135–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.006

-

22. Froessler B, Cocchiaro C, Saadat-Gilani K, Hodyl N and Dekker G (2013). Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral iron ferrous sulfate for antenatal and postpartum iron deficiency anemia: A randomized trial. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 26(7):654–659. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2012.746299

-

23. Kochhar PK, Kaundal A and Ghosh P (2013). Intravenous iron sucrose versus oral iron in treatment of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 39(2):504–510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01982.x

-

24. Hashmi Z, Bashir G, Azeem P and Shah S (2006). Effectiveness of intra-venous iron sucrose complex versus intra-muscular iron sorbitol in iron deficiency anemia. Annals of Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences 2(3):188–191.

-

25. Lee JI, Lee JA and Lim HS (2005). Effect of time of initiation and dose of prenatal iron and folic acid supplementation on iron and folate nutriture of Korean women during pregnancy. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 82(4):843–849.

-

26. Bhandal N and Russell R (2006). Intravenous versus oral iron therapy for postpartum anaemia. BJOG 113(11):1248–1252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01062.x

-

27. Giannoulis C, Daniilidis A, Tantanasis T, Dinas K and Tzafettas J (2009). Intravenous administration of iron sucrose for treating anemia in postpartum women. Hippokratia 13(1):38–40. http://www.hippokratia.gr/index.php/archives/volume-13-2009/issue-1/686-intravenous-administration-of-iron-sucrose-for-treating-anemia-in-postpartum-women

-

28. Jain G, Palaria U and Jha SK (2013). Intravenous iron in postpartum anemia. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 63(1):45–48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0240-y

-

29. Mumtaz A and Farooq F (2011). Comparison for effects of intravenous versus oral iron therapy for postpartum anemia. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences 5(1):116–120.

-

30. Seid MH, Derman RJ, Baker JB, Banach W, Goldberg C and Rogers R (2008). Ferric carboxymaltose injection in the treatment of postpartum iron deficiency anemia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 199(4):435.e1-435.e7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.046

-

31. Verma S, Inamdar SA and Malhotra N (2011). Intravenous iron therapy versus oral iron in postpartum patients in rural area. SAFOG 3(2):67–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10006-1131

-

32. Khalafallah A, Dennis A, Bates J, Bates G, Robertson IK, Smith L, et al. (2010). A prospective randomized, controlled trial of intravenous versus oral iron for moderate iron deficiency anaemia of pregnancy. Journal of Internal Medicine 268(3):286–295.

-

33. Deeba S, Purandare SV and Sathe AV (2012). Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy: Intravenous versus oral route. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 62(3):317–321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0222-0

-

34. Singh S and Singh PK (2013). A study to compare the efficacy and safety of intravenous iron sucrose and intramuscular iron sorbitol therapy for anemia during pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 63(1):18–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0248-3

-

35. Zutschi V, Batra S, Ahmad SS, Khera N, Chauhan G and Ghandi G (2004). Injectable iron supplementation instead of oral therapy for antenatal care. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India 54(1):37–38.

-

36. Ogunbode O, Damole IO and Oluboyede OA (1980). Iron supplement during pregnancy using three different iron regimens. Current Therapeutic Research, Clinical and Experimental 27(1):75–80.

-

37. Kumar A, Jain S, Singh NP and Singh T (2005). Oral versus high dose parenteral iron supplementation in pregnancy. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: the Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 89(1):7–13.

-

38. Taylor DJ, Mallen C, McDougall N and Lind T (1982). Effect of iron supplementation on serum ferritin levels during and after pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 89(12):1011–1017.

-

39. Christian P, Shrestha J, LeClerq SC, Khatry SK, Jiang T, Wagner T, et al. (2003). Supplementation with micronutrients in addition to iron and folic acid does not further improve the hematologic status of pregnant women in rural Nepal. The Journal of Nutrition 133(11):3492–3498.

-

40. Dodd J, Dare MR and Middleton P (2004). Treatment for women with postpartum iron deficiency anaemia. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4):CD004222.

-

41. Krafft A and Breymann C (2011). Iron sucrose with and without recombinant erythropoietin for the treatment of severe postpartum anemia: A prospective, randomized, open-label study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 37(2):119–124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01328.x

-

42. Wagstrom E, Akesson A, Van Rooijen M, Larson B and Bremme K (2007). Erythropoietin and intravenous iron therapy in postpartum anaemia. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 86(8):957–962. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016340701446157

-

43. Pasquier P, Gayat E, Rackelboom T, La Rosa J, Tashkandi A, Tesniere A, et al. (2013). An observational study of the fresh frozen plasma: Red blood cell ratio in postpartum hemorrhage. Anesthesia and Analgesia 116(1):155–161. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23223094

-

44. Rainaldi MP, Tazzari PL, Scagliarini G, Borghi B and Conte R (1998). Blood salvage during caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 80(2):195-198. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9602584

-

45. Malik S, Brooks H and Singhal T (2010). Cell saver use in obstetrics. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 30(8):826–828. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2010.511727

-

46. National Blood Authority (NBA) (2014). Guidance for the provision of intraoperative cell salvage. NBA, Canberra, Australia. http://blood.gov.au/ics

-

47. Dilauro MD, Dason S and Athreya S (2012). Prophylactic balloon occlusion of internal iliac arteries in women with placenta accreta: Literature review and analysis. Clinical Radiology 67(6):515–520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2011.10.031

-

48. Omar HR, Karlnoski R, Mangar D, Patel R, Hoffman M and Camporesi E (2012). Staged endovascular balloon occlusion versus conventional approach for patients with abnormal placentation: A literature review. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 28(4):247–254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2011.0096

-

49. Bodner LJ, Nosher JL, Gribbin C, Siegel RL, Beale S and Scorza W (2006). Balloon-assisted occlusion of the internal iliac arteries in patients with placenta accreta/percreta. CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology 29(3):354–361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00270-005-0023-2

-

50. Levine AB, Kuhlman K and Bonn J (1999). Placenta accreta: Comparison of cases managed with and without pelvic artery balloon catheters. Journal of Maternal-Fetal Medicine 8(4):173–176. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10406301

-

51. Shrivastava V, Nageotte M, Major C, Haydon M and Wing D (2007). Case-control comparison of cesarean hysterectomy with and without prophylactic placement of intravascular balloon catheters for placenta accreta. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 197(4):402–405.

-

52. Ballas J, Hull AD, Saenz C, Warshak CR, Roberts AC, Resnik RR, et al. (2012). Preoperative intravascular balloon catheters and surgical outcomes in pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta: A management paradox. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 207(3):216.e1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.007

-

53. Descargues G, Mauger Tinlot F, Douvrin F, Clavier E, Lemoine JP and Marpeau L (2004). Menses, fertility and pregnancy after arterial embolization for the control of postpartum haemorrhage. Hum Reprod 19(2):339-343. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14747177

-

54. Department of Health SA (2012). Balloon tamponade and uterine packing for major PPH. South Australian Perinatal Practice Guidelines. http://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/1bf9b8004ee1dd0aacefadd150ce4f37/Balloon-tamponade-uterine-pack-PPH-WCHN-PPG-22052012.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=1bf9b8004ee1dd0aacefadd150ce4f37&CACHE=NONE

-

55. Ahonen J, Jokela R and Korttila K (2007). An open non-randomized study of recombinant activated factor VII in major postpartum haemorrhage. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 51(7):929–936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01323.x

-

56. Hossain N, Shamsi T, Haider S, Soomro N, Khan NH, Memon GU, et al. (2007). Use of recombinant activated factor VII for massive postpartum hemorrhage. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 86(10):1200–1206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016340701619324

-

57. Kalina M, Tinkoff G and Fulda G (2011). Massive postpartum hemorrhage: recombinant factor VIIa use is safe but not effective. Delaware medical journal 83(4):109–113.

-

58. Abdel-Aleem H, Alhusaini TK, Abdel-Aleem MA, Menoufy M and Gulmezoglu AM (2013). Effectiveness of tranexamic acid on blood loss in patients undergoing elective cesarean section: randomized clinical trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 26(17):1705-1709. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23574458

-

59. Gai MY, Wu LF, Su QF and Tatsumoto K (2004). Clinical observation of blood loss reduced by tranexamic acid during and after caesarian section: A multi-center, randomized trial. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 112(2):154–157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00287-2

-

60. Gungorduk K, Yildirim G, Asicioglu O, Gungorduk OC, Sudolmus S and Ark C (2011). Efficacy of intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss after elective cesarean section: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Perinatology 28(3): 233—239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1268238

-

61. Senturk MB, Cakmak Y, Yildiz G and Yildiz P (2013). Tranexamic acid for cesarean section: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 287(4):641–645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2624-8

-

62. Xu J, Gao W and Ju Y (2013). Tranexamic acid for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean section: A double-blind randomization trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 287(3):463–468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2593-y

-

63. Gungorduk K, Asicioglu O, Yildirim G, Ark C, Tekirdag A and Besimoglu B (2013). Can intravenous injection of tranexamic acid be used in routine practice with active management of the third stage of labor in vaginal delivery? A randomized controlled study. American Journal of Perinatology 30(5):407–413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1326986

-

64. Ducloy-Bouthors AS, Jude B, Duhamel A, Broisin F, Huissoud C, Keita-Meyer H, et al. (2011). High-dose tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in postpartum haemorrhage. Critical care 15(2):R117.

-

65. Lindoff C, Rybo G and Astedt B (1993). Treatment with tranexamic acid during pregnancy, and the risk of thrombo-embolic complications. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 70(2):238–240.

-

66. Roberts I, Shakur H, Ker K and Coats T (2011). Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD004896. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21249666

-

67. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2011). The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Cat. No. IHW 42, AIHW, Canberra.

-

68. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Perfil de salud de indígenas. Colombia. 2016

-

69. Holt DC, McCarthy JS and Carapetis JR (2010). Parasitic diseases of remote Indigenous communities in Australia. Int J Parasitol 40(10):1119-1126. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20412810

-

70. Windsor HM, Abioye-Kuteyi EA, Leber JM, Morrow SD, Bulsara MK and Marshall BJ (2005). Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Indigenous Western Australians: comparison between urban and remote rural populations. Med J Aust 182(5):210-213. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15748129

-

71. Li Z, Zeki R, Hilder L and Sullivan EA (2011). Australia’s mothers and babies. Perinatal statistics series, No. 28, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

-

72. Roberts CL, Ford JB, Thompson JF and Morris JM (2009). Population rates of haemorrhage and transfusions among obstetric patients in NSW: a short communication. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 49(3):296-298. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19566563

-

73. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la prevención, detección temprana y tratamiento del embarazo, parto o puerperio, 2013

-

74. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1989). CDC criteria for anemia in children and childbearing-aged women. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 38(22):400–404.

-

75. World Health Organization (WHO) (1968). Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Technical Report Series, No. 405, WHO, Geneva.

-

76. World Health Organization (WHO) (2001). Iron deficiency anaemia. Assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programme managers, WHO, Geneva.

-

77. Klajnbard A, Szecsi PB, Colov NP, Andersen MR, Jorgensen M, Bjorngaard B, et al. (2010). Laboratory reference intervals during pregnancy, delivery and the early postpartum period. Clin Chem Lab Med 48(2):237-248. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19943809

-

78. Erber WN, Buck AM and Threlfall TJ (2004). The haematology of indigenous Australians. Haematology 9(5–6):339–350.

-

79. Haider BA, Olofin I, Wang M, Spiegelman D, Ezzati M, Fawzi WW, et al. (2013). Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 346:f3443.

-

80. Arnold DL, Williams MA, Miller RS, Qiu C and Sorensen TK (2009). Iron deficiency anemia, cigarette smoking and risk of abruptio placentae. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 35(3):446–452.

-

81. Brabin BJ, Hakimi M, and Pelletier D (2001). An analysis of anemia and pregnancy-related maternal mortality. Journal of Nutrition 13(25–2):604S–614S.

-

82. Corwin EJ, Murray-Kolb LE and Beard JL (2003). Low hemoglobin level is a risk factor for postpartum depression. The Journal of Nutrition 133(12):4139–4142.

-

83. Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson A and Cnattingius S (2000). Maternal hemoglobin concentration during pregnancy and risk of stillbirth. Journal of the American Medical Association 284(20):2611–2617.

-

84. World Health Organization (WHO) (1992). The prevalence of anaemia in women: A tabulation of available information (WHO/MCH/MSM/92), WHO, Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme, Division of Family Health, Geneva.

-

85. Khambalia AZ, Aimone AM and Zlotkin SH (2011). Burden of anemia among indigenous populations. Nutr Rev 69(12):693-719. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22133195

-

86. Lewis LN, Hickey M, Doherty DA and Skinner SR (2009). How do pregnancy outcomes differ in teenage mothers? A Western Australian study. Med J Aust 190(10):537-541. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19450192

-

87. Chan A, Roder D and Macharper T (1988). Obstetric profiles of immigrant women from non-English speaking countries in South Australia, 1981-1983. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 28(2):90-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3228416

-

88. Nybo M, Friis-Hansen L, Felding P and Milman N (2007). Higher prevalence of anemia among pregnant immigrant women compared to pregnant ethnic Danish women. Ann Hematol 86(9):647-651. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17486340

-

89. Noronha J, Bhaduri A, Vinod Bhat H and Kamath A (2010). Maternal risk factors and anaemia in pregnancy: a prospective retrospective cohort study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 30(2):132–136.

-

90. Australia and New Zealand Society of Blood Transfusion (ANZSBT) (2007). Guidelines for blood grouping & antibody screening in the antenatal & perinatal setting. 3rd Edition. http://www.anzsbt.org.au/publications

-

91. Australian Government Department of Health (2012). National maternity services capability framework.

-

92. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RANZCOG) (2014). Management of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) (revision of 2011 publication), RANZCOG. http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/college-statements-guidelines.html

-

93. Protocolo del INS

-

94. McLintock C and James AH (2011). Obstetric hemorrhage. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 9(8):1441-1451.

-

95. Metcalfe AR (2012). Maternal morbidity data in Australia: An assessment of the feasibility of standardized collection. Cat. No. PER 56, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Canberra.

-

96. Keeling D, Tait C and Makris M (2008). Guideline on the selection and use of therapeutic products to treat haemophilia and other hereditary bleeding disorders. A United Kingdom Haemophilia Center Doctors’ Organisation (UKHCDO) guideline approved by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Haemophilia 14(4):671-684. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18422612

-

97. AHCDO (2007). Guidelines for management of pregnancy and delivery in women who are either carriers or patients with bleeding disorders, Australian Haemophilia Centre Directors’ Organisation (AHCDO), Victoria.

-

98. James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, Edlund M, Federici AB, Halimeh S, et al. (2009). Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 201(1):12.e11-12.e18.

-

99. Australia and New Zealand Society of Blood Transfusion (ANZSBT) (2007). Guidelines for pretransfusion laboratory practice. 5th Edition. http://www.anzsbt.org.au/publications/documents/plp_guidelines_mar07.pdf

-

100. (2009). Coronial inquest into the death of Rebecca Murray. File No 615/2007, Coronial Jurisdiction of New South Wales.

-

101. Stock O and Beckman M (2014). Why group and save? Blood transfusion at low risk elective caesarean section. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 54(3):279-282

-

102. Lombardi G, Garofoli F and Stronati M (2010). Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: treatment, sequelae and follow-up. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 23(S3):45-48.

-

103. Johnson J, Anderson B and Pass RF (2012). Prevention of maternal and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 55(2):521-530.

-

104. Advisory Committee on the Safety of Blood (2012). Cytomegalovirus tested blood components: Position Statement. SaBTO report of the Cytomegalovirus Steering Group, Department of Health. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215125/dh_133086.pdf

-

105. van Wamelen DJ, Klumper FJ, de Haas M, Meerman RH, van Kamp IL and Oepkes D (2007). Obstetric history and antibody titer in estimating severity of Kell alloimmunization in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 109(5):1093-1098.

-

106. Department of Health NSW (2010). Maternity – prevention, early recognition & management of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH). Policy Directive, Department of Health NSW. http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2010/PD2010_064.html

-

107. Allard S, Green L and Hunt BJ (2014). How we manage the haematological aspects of major obstetric haemorrhage. British Journal of Haematology 164(2):177–188.

-

108. Solomon C, Collis RE and Collins PW (2012). Haemostatic monitoring during postpartum haemorrhage and implications for management. British Journal of Anaesthesia 109(6):851–863.

-

109. Wikkelsoe AJ, Afshari A, Stensballe J, Langhoff-Roos J, Albrechtsen C, Ekelund K, et al. (2012). The FIB-PPH trial: Fibrinogen concentrate as initial treatment for postpartum haemorrhage: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 13:110.

-

110. Charbit B, Mandelbrot L, Samain E, Baron G, Haddaoui B, Keita H, et al. (2007). The decrease of fibrinogen is an early predictor of the severity of postpartum hemorrhage. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 5(2):266–273.

-

111. de Lloyd L, Bovington R, Kaye A, Collis RE, Rayment R, Sanders J, et al. (2011). Standard haemostatic tests following major obstetric haemorrhage. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 20(2):135–141.

-

112. Cortet M, Deneux-Tharaux C, Dupont C, Colin C, Rudigoz RC, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. (2012). Association between fibrinogen level and severity of postpartum haemorrhage: secondary analysis of a prospective trial. Br J Anaesth 108(6):984-989. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22490316

-

113. Bell SF, Rayment R, Collins PW and Collis RE (2010). The use of fibrinogen concentrate to correct hypofibrinogenaemia rapidly during obstetric haemorrhage. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 19(2):218–223.

-

114. Glover NJ, Collis RE and Collins P (2010). Fibrinogen concentrate use during major obstetric haemorrhage. Anaesthesia 65(12):1229–1230.

-

115. Massiah N, Athimulam S, Loo C, Okolo S and Yoong W (2007). Obstetric care of Jehovah’s Witnesses: A 14-year observational study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 276(4):339–343.

-

116. van Wolfswinkel ME, Zwart JJ, Schutte JM, Duvekot JJ, Pel M and Van Roosmalen J (2009). Maternal mortality and serious maternal morbidity in Jehovah’s witnesses in the Netherlands. BJOG 116(8):1103–1108, discussion 1108–1110.

-

117. Mitra B, Cameron PA, Gruen RL, Mori A, Fitzgerald M and Street A (2011). The definition of massive transfusion in trauma: a critical variable in examining evidence for resuscitation. Eur J Emerg Med 18(3):137-142. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21164344