Aunque una reducción por corto tiempo de chal es una consecuencia indeseable, el impacto a largo plazo no ha sido bien estudiado133. El efecto no favorable sobre las lipoproteínas es acompañado por efectos benéficos en factores de coagulación consistente en aumento de la fibrinolisis y no cambios en la coagulación134,135. En general es posible que alguna actividad favorable en el sistema cardiovascular sea conservada. Experimentalmente, la tibolona reduce los signos de isquemia y prolonga el tiempo a angina en una manera similar a los estrógenos136. La tibolona también tiene un impacto benéfico en estudios a corto plazo en la resistencia a la insulina en mujeres normales con diabetes no insulina dependiente137,138. La tibolona no tiene efecto en la presión arterial139.

Opciones de tratamiento. Resumen

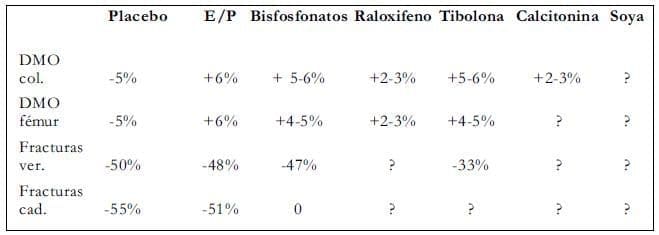

Reafirmamos que hay datos disponibles de prevención de osteoporosis y fracturas relacionadas con osteoporosis, con la terapia hormonal y alendronato. La ausencia de efecto en las fracturas de cadera después de tres años de raloxifeno causa preocupación. Para tibolona y fitoestrógenos, no hay datos de fracturas. Basados en la respuesta de la densidad ósea, podemos predecir que tibolona podría tener un impacto en la incidencia de fracturas. Debemos tener en mente que los datos de fracturas asociadas con alendronatos se derivan de mujeres con osteoporosis.

La calcitonina regula el calcio del plasma inhibiendo la resorción ósea y puede ser usada en pacientes en quienes la terapia hormonal está contraindicada. Dada en inyección subcutánea en una dosis de 100 UI diarias a mujeres con menopausia temprana tiene el mismo efecto que los estrógenos en la conservación de la densidad ósea140. Estudios con calcitonina de salmón de liberación intranasal (200 UI diarias) indican que puede ser igualmente efectiva141. La calcitonina de salmón en aerosol nasal redujo el riesgo de fracturas en un 33%142. El tratamiento con calcitonina puede combinarse con vitamina D y suplemento de calcio. Las desventajas son el alto costo y las potenciales reacciones inmunológicas a la calcitonina no humana. La calcitonina humana está disponible, pero la calcitonina recombinante de salmón es más potente. Una preparación oral estará próximamente disponible.

Manejo en las que no responden a terapia hormonal

Hay un porcentaje de mujeres en terapia hormonal (5% a 10%), dependiendo de la adherencia al tratamiento, quienes continúan perdiendo hueso y experimentando fracturas60,62,145. Es importante medir la densidad ósea en mujeres tratadas cuando están en su sexta década de edad para detectar las pobres respondedoras. En promedio, hay cerca del 10% al 15% de mujeres con pérdida de hueso a pesar de habérseles prescrito terapia hormonal. Un estudio clínico terminado a cinco años reportó una prevalencia de pobre respuesta basada en la densidad ósea de 11% en la columna y 26% en la cadera147. Como se esperaba, fumar y el bajo peso fueron hallazgos comunes entre las pobres respondedoras, pero las características más impresionantes fueron niveles de estradiol bajo y FSH alta. Es apenas lógico que haya un grupo de mujeres quienes metabolizan y aclaran estrógenos administrados a una tasa mayor, y por lo tanto requieren de dosis más altas para un efecto protector sostenido en el hueso. Indudablemente, se han documentado considerables variaciones en los niveles de estradiol en individuos que reciben terapia hormonal oral y transdérmica148,149. Presentaciones en el mercado por casas farmacéuticas dan niveles promedio, sugiriendo niveles estables y mantenimiento plano de sangre; sin embargo, los rangos, que son amplios, no se revelan. Una ayuda para la individualización de la terapia hormonal es determinar la dosis apropiada para el objetivo deseado; en el caso del hueso, los niveles mínimos de estradiol se deben dar de 40-60 pg/mL, y un rango práctico para las muestras de sangre durante las horas de oficina de un paciente tomando su medicación en la noche debe ser 50-100 pg/mL.

Dos años de efectos óseos en mujeres con osteoporosis 51,52,54,56,121,125,142-145

Como los clínicos y la industria farmacéutica promueven bajas dosis de estrógenos con la atractiva noción de que menos es más seguro, debe esperarse una alta tasa de pobres respondedoras medida por la densidad ósea. Estamos sugiriendo que, una vez una pobre respondedora sea detectada por la medición de densidad ósea, se indica una medición de estrógenos, utilizando la concentración de estradiol en sangre. Posteriormente podemos enfatizar que la apropiada detección e investigación conformarán que una relativa dosis de bajos niveles de estradiol es la causa de la mayoría de los casos de pobre respuesta. Las medidas de pH vaginal en las paredes laterales de la vagina son muy simples y baratas. Ha sido impresionante en mi experiencia y la de otros cómo un pH ácido (menos de 4.5) se correlaciona con la administración de estrógenos150,151. Este podría ser el mejor método para medir lo adecuado de la terapia estrogénica. La medición de citología vaginal no es útil. La mucosa vaginal es muy sensible a los estrógenos para permitir una medición de dosisrespuesta.

La medida de densidad ósea puede también detectar individuos que están respondiendo pobremente a los bisfosfonatos o al raloxifeno. Dos consideraciones debemos tener en mente. Primero, establecer que la ingesta apropiada de la medicación se esté practicando con buena aceptación. Segundo, descartar otra causa de pérdida ósea y estar seguros de que la suplementación con calcio y vitamina D es adecuada.

En una mujer en quien se demuestra pérdida ósea a pesar de recibir terapia hormonal, se recomiendan los siguientes pasos:

• Chequear la adherencia y medir niveles de estrógenos en sangre: ajustar la dosis de acuerdo a los títulos de estradiol.

• Descartar otras causas de pérdida ósea:

Desórdenes alimenticios.

Enfermedades crónicas: renal y hepática.

Desórdenes endocrinos: exceso de glucocorticoides.

Hipertiroidismo.

Deficiencia estrogénica.

Hiperparatiroidismo.

• Nutricional: deficiencias de calcio, fósforo y vitamina D.

• Agregar un bifosfonato si la pobre respuesta continúa a pesar de mantener los niveles sanguíneos de estradiol en el rango de los 50-100 pg/mL.

• Seguir con mediciones de marcadores de densidad ósea.

Referencias

1. National Osteoporosis Foundation. https:// www.nof.org 1999.

2. Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston Jr CC, et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 1997; 12: 1761-1768.

3. Johnston CC, Jr., Slemenda CW, Melton III LJ. Clinical use of bone densitometry. New Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1105.

4. Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. Lancet 1993; 341: 72.

5. Rubin SM, Cummings SR. Results of bone densitometry affect women’s decisions about taking measures to prevent fractures. Ann Int Med 1992; 116: 990.

6. Silverman SL, Greenwald M, Klein RA, Drinkwater BL. Effect of bone density information on decisions about hormone replacement therapy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 1997; 89: 321-325.

7. Chow RK, Harrison JE, Brown CF, Hajek V. Physical fitness effect on bone mass in postmenopausal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67: 231.

8. Dalsky G, Stocke KS, Ehsani AA, Slatopolsky E, Lee WC, Birjes J, Jr. Weight-bearing exercise training and lumbar bone mineral content in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 1988; 108: 824.

9. Cavanagh DJ, Cann CE. Brisk walking does not stop bone loss in postmenopausal women. Bone 1988; 9: 201.

10. Brooke-Wavell K, Jones PRM, Hardman AE. Brisk walking reduces calcaneal bone loss in post-menopausal women. Clin Sci 1997; 92: 75-80.

11. Ebrahim S, Thompson PW, Baskaran V, Evans K. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of brisk walking in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Age Ageing 1997; 26: 253-260.

12. Kohrt WM, Snead DB, Slatopolsky E, Birge Jr SJ. Additive effects of weight-bearing exercise and estrogen on bone mineral density in older women. J Bone Miner Res 1995; 10: 1303-1311.

13. Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. New Engl J Med 1995; 332: 767-773.

14. Prince RL, Smith M, Dick IM, et al. Prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a comparative study of exercise, calcium supplementation, and hormone-replacement therapy. New Engl J Med 1991; 325: 1189-1195.

15. Lukert BP, Johnson BE, Robinson RG. Estrogen and progesterone replacement therapy reduces glucocorticoid-induced bone loss. J Bone Miner Res 1992; 7: 1063.

16. Hall GM, Daniels M, Doyle DV, Spector TD. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on bone mass in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with and without steroids. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37: 1499-1505.

17. Saag KG, Emkey R, Schnitzer TJ, et al. Alendronate for the prevention and treatment of glucocoricoid-induced osteoporosis. New Engl J Med 1998; 339: 292-299.

18. Reid IR, Ames RW, Evans MC, Gamble GD, Sharpe SJ. Long-term effects of calcium supplementation on bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med 1995; 98: 331-335.

19. Recker RR, Hinders S, Davies KM, et al. Correcting calcium nutritional deficiency prevents spine fractures in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 1996; 11: 1961-1966.

20. Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. New Engl J Med 1997; 337: 670-676.

21. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Optimal Calcium Intake. Optimal calcium intake. JAMA 1994; 272: 1942.

22. Hasling C, Charles P, Jensen FT, Mosekilde L. Calcium metabolism in postmenopausal osteoporosis: the influence of dietary calcium and net absorbed calcium. J Bone Min Res 1990; 5: 939.

23. Heaney RP, Recker RR. Distribution of calcium absorption in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr 1986; 43: 299.

24. Ettinger B, Genant HK, Steiger P, Madvig P. Low-dosage micronized 17b-estradiol prevents bone loss in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 166: 479.

25. Lloyd T, Andon MB, Rollings N, et al. Calcium supplementation and bone mineral density in adolescent girls. JAMA 1993; 270: 841.

26. Cadogan J, Eastell R, Jones N, Barker ME. Milk intake and bone mineral acquisition in adolescent girls: randomised, controlled intervention trial. Br Med J 1997; 315: 1255- 1260.

27. Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. New Engl J Med 2006; 354: 684-696.

28. Heikinheimo RJ, Inkovaara JA, Harju EJ, et al. Annual injection of vitamin D and fractures of aged bones. Calcif Tissue Int 1992; 51: 105.

29. Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, et al. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. New Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1637.

30. Tilyard MW, Spears GFS, Thomson J, Dovey S. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis with calcitriol or calcium. New Engl J Med 1992; 326: 357.

31. Ooms ME, Roos JC, Bezemer PD, et al. Prevention of bone loss by vitamin D supplementation in elderly women: a randomized double-blind trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80: 1052.

32. Rosen CJ, Morrison A, Zhou H, et al. Elderly women in northern New England exhibit seasonal changes in bone mineral density and calciotropic hormones. Bone Mineral 1994; 25: 83.

33. Thomas MK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Thadhani RI, et al. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. New Engl J Med 1998; 338: 777-783.

34. Holick MF. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc 2006; 81: 353-373.

35. Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R. Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporosis Int 2005; 16: 713-716.

36. Feskanich D, Singh V, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Vitamin A intake and hip fractures among postmenopausal women. JAMA 2002; 287: 47-54.

37. Komulainen MH, Kröger H, Tuppurainen MT, et al. HRT and Vit D in prevention of non-vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women; a 5 year randomized trial. Maturitas 1998; 31: 45-54.

38. Mosekilde L, Beck-Nielsen H, Sørensen OH, et al. Hormonal replacement therapy reduces forearm fracture incidence in recent postmenopausal women – results of the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study.Maturitas 2000; 36: 181-193.

39. Cauley J, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density. The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. JAMA 2003; 290: 1729-1738.

40. The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2004; 291: 1707-1712.

41. Weiss NC, Ure CL, Ballard JH, Williams AR, Daling JR. Decreased risk of fractures of the hip and lower forearm with postmenopausal use of estrogen. New Engl J Med 1980; 303: 1195.

42. Ettinger B, Genant HK, Cann CE. Longterm estrogen replacement therapy prevents bone loss and fractures. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102: 319.

43. Kiel DP, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Wilson PWF, Moskowitz MA. Hip fracture and the use of estrogen in postmenopausal women: the Framingham Study. New Engl J Med 1987; 317: 1169.

44. Michaëlsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of hip fracture: population based case-control study. Br Med J 1998; 316: 1858-1863.

45. Riggs BL, Seeman E, Hodgson SF, Taves DR, O’Fallon WM. Effect of the fluoride/calcium regimen on vertebral fracture occurrence in postmenopausal osteoporosis. New Engl J Med 1982; 306: 446.

46. Quigley MET, Martin PL, Burnier AM, Brooks P. Estrogen therapy arrests bone loss in elderly women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987; 156: 1516.

47. Lafferty FW, Fiske ME. Postmenopausal estrogen replacement: a long-term cohort study. Am J Med 1994; 97: 66.

48. Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Kiel DP, Wilson PWF, Anderson JJ. The effect of postmenopausal estrogen therapy on bone density in elderly women. New Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1141-1146.

49. Cauley JA, Seeley DG, Enbsrud K, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy and fractures in older women. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122: 9- 16.

50. Lindsay R, MacLean A, Kraszewski A, Clark AC, Garwood J. Bone response to termination of estrogen treatment. Lancet 1978; i: 1325.

51. Horsman A, Nordin BEC, Crilly RG. Effect on bone of withdrawal of estrogen therapy. Lancet 1979; ii: 33.

52. Christiansen C, Christiansen MS, Transbol IB. Bone mass in postmenopausal women after withdrawal of oestrogen/gestagen replacement therapy. Lancet 1981; i: 459.

53. Trémollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Ribot C. Withdrawal of hormone replacement therapy is associated with significant vertebral bone loss in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2001; 12: 385-390.

54. Sornay-Rendu E, Garnero P, Munoz F, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD. Effect of withdrawal of hormone replacement therapy on bone mass and bone turnover: the OFELY study. Bone 2003; 33: 159-166.

55. Greendale GA, Espeland M, Slone S, Marcus R, Barrett-Connor E, PEPI Safety Follow- Up Study (PSFS) Investigators. Bone mass response to discontinuation of long-term hormone replacement therapy: results from the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Safety Follow-up Study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 25: 665-672.

56. Gallagher JC, Rapuri PB, Haynatzki G, Detter JR. Effect of discontinuation of estrogen, calcitriol, and the combination of both on bone density and bone markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 4914-4923.

57. Schneider DL, Barrett-Connor EL, Morton DJ. Timing of postmenopausal estrogen for optimal bone mineral density. The Rancho Bernardo Study. JAMA 1997; 277: 543- 547.

58. Barrett-Conner E, Wehren LE, Siris ES, et al. Recency and duration of postmenopausal hormone therapy: effects on bone mineral density and fracture risk in the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA) study. Menopause 2003; 10: 412-419.

59. Stevenson JC, Cust MP, Gangar KF, Hillard TC, Lees B, Whitehead MI. Effects of transdermal versus oral hormone replacement therapy on bone density in spine and proximal femur in postmenopausal women. Lancet 1990; 336: 1327.

60. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone therapy on bone mineral density: results from the Postmenopausal Estrogen/ Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA 1996; 276: 1389-1396.

61. Eiken P, Kolthoff N, Nielsen SP. Effect of 10 years’ hormone replacement therapy on bone mineral content in postmenopausal women. Bone 1996; 19: 191S-193S.

62. Nelson HD, Rizzo J, Harris E, et al. Osteoporosis and fractures in postmenopausal women using estrogens. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 2278-2284.

63. Naessén T, Persson I, Thor L, Mallmin H, Ljunghall S, Bergstrom R. Maintained bone density at advanced ages after long-term treatment with low-dose estradiol implants. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993; 100: 454.

64. Armamento-Villareal R, Civitelli R. Estrogen action on the bone mass of postmenopausal women is dependent on body mass and initial bone density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80: 776.

65. Villareal DT, Binder EF, Williams DB, Schechtman KB, Yarasheski KE, Kohrt WM. Bone mineral density response to estrogen replacement in frail elderly women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286: 815-820.

66. Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, Ensrud KE, Bauer DC, Ettinger B, for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Timing of estrogen replacement therapy for optimal osteoporosis prevention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 5700-5705.

67. Lindsay R, Hart DM, Clark DM. The minimum effective dose of estrogen for postmenopausal bone loss. Obstet Gynecol 1984; 63: 759.

68. O’Connell MB. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacologic variation between different estrogen products. J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 35(Suppl 9): 18S-24S.

69. Reginster JY, Sarlet N, Deroisy R, Albert A, Gaspard U, Franchimont P. Minimal levels of serum estradiol prevent postmenopausal bone loss. Calcif Tissue Int 1992; 51: 340-343.

70. Ettinger B, Pressman A, Sklarin P, Bauer DC, Cauley JA, Cummings SR. Associations between low levels of serum estradiol, bone density, and fractures among elderly women: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 2239-2243.

71. Cummings SR, Browner WS, Bauer D, et al. Endogenous hormones and the risk of hip and vertebral fractures among older women. New Engl J Med 1998; 339: 733-38.

72. Naessen T, Berglund L, Ulmsten U. Bone loss in elderly women prevented by ultralow dosesof parenteral 17beta-estradiol. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177: 115-119.

73. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kleerekoper M,Pickar JH. Effect of lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens with and without medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone in early postmenopausal women. JAMA 2002; 287: 2668-2676.

74. Garnett T, Studd J, Watson N, Savvas M, Leather A. The effects of plasma estradiol levels on increases in vertebral and femoral bone density following therapy with estradiol and estradiol with testosterone implants. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 968-972f.

75. Watts NB, Notelovitz M, Timmons MC, Addison WA, Wiita B, Downey LJ. Comparison of oral estrogens and estrogens plus androgens on bone mineral density, menopausal symptoms, and lipid-lipoprotein profiles in surgical menopause. Obstet Gynecol 1995; 85: 529-537.

76. Davis SR, McCloud P, Strauss BJG, Burger H. Testosterone enhances estradiol’s effects on postmenopausal bone density and sexuality. Maturitas 1995; 21: 227-36.

77. Barrett-Conner E, Young RH, Notelovitz M, et al. A two-year, double-blind comparison of estrogen-androgen and conjugated estrogens in surgically menopausal women. Effects on bone mineral density, symptoms and lipid profiles. J Reprod Med 1999; 44: 1012-1020.

78. de Groen PC, Lubbe DF, Hirsch LJ, et al. Esophagitis associated with the use of alendronate. New Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1016-1021.

79. Bauer DC, Black D, Ensrud K, et al. Upper gastrointestinal tract safety profile of alendronate: the Fracture Intervention Trial. Arch Intern Med 2000; 28: 517-525.

80. Lowe CE, Depew WT, Vanner SJ, Paterson WG, Meddings JB. Upper gastrointestinal toxicity of alendronate. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 634-640.

81. Mortensen L, Charles P, Bekker PJ, Digennaro J, Johnston CC, Jr. Risedronate increases bone mass in an early postmenopausal population: two years of treatment plus one year of follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 396-402.

82. Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized, controlled trial. JAMA 1999; 282: 1344-1352.

83. McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. New Eng J Med 2001; 344: 333-340.

84. Foidart JM, Wuttke W, Bouw GM, Gerlinger C, Heithecker R. A comparative investigation of contraceptive reliability, cycle control and tolerance of two monophasic oral contraceptives containing either drospirenone or desogestrel. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2000; 5: 124-134.

85. Fogelman I, Ribot C, Smith R, et al. Risedronate reverses bone loss in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: results from a multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 1895-1900.

86. Schnitzer T, Bone HG, Crepaldi G, et al. Therapeutic equivalence of alendronate 70 mg once-weekly and alendronate 10 mg daily in the treatment of osteoporosis. Alendronate Once-Weekly Study Group. Aging 2000; 12: 1-12.

87. Brown JP, Kendler DL, McClung MR, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of risedronate once a week for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2002; 71: 103-111.

88. Luckey MM, Gilchrist N, Bone HG, et al. Therapeutic equivalence of alendronate 35 milligrams once weekly and 5 milligrams daily in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 101: 711-721.

89. Blumel JE, Castelo-Branco C, de la Cuadra G, Maciver L, Moreno M, Haya J. Alendronate daily, weekly in conventional tablets and weekly in enteric tablets: preliminary study on the effects in bone turnover markers and incidence of side effects. J Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 23: 278-281.

90. Rizzoli R, Greenspan SL, Bone G, III., et al. Two-year results of once-weekly administration of alendronate 70 mg for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Mineral Res 2002; 17: 1988-1996.

91. Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet 1996; 348: 1535-1541.

92. Karpf DB, Shapiro DR, Seeman E, et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures by alendronate. JAMA 1997; 277: 1159-1164.

93. Black DM, Thompson DE, Bauer DC, et al. Fracture risk reduction with alendronate in women with osteoporosis: the Fracture Intervention Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 4118-4124.

94. Hosking D, Chilvers CED, Christiansen C, et al. Prevention of bone loss with alendronate in postmenopausal women under 60 years of age. New Engl J Med 1998; 338: 485-492.

95. McClung M, Clemmesen B, Daifotis A, et al. Alendronate prevents postmenopausal bone loss in women without osteoporosis: a doubleblind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128: 253-261.

96. Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures. Results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998; 280: 2077- 2082.

97. Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int 2000; 11: 83-91.

98. Sorensen OH, Crawford GM, Mulder H, et al. Long-term efficacy of risedronate: a 5-year placebo-controlled clinical experience. Bone 2003; 32: 120-126.

99. Lindsay R, Cosman F, Lobo RA, et al. Addition of alendronate to ongoing hormone replacement therapy in the treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84: 3076-3081.

100. Greenspan S, Bankhurst A, Bell N, et al. Effects of alendronate and estrogen, alone or in combination, on bone mass and turnover in postmenopausal osteoporosis (abstract). Bone 1998; 23(Suppl 5): S174.

101. Harris ST, Eriksen EF, Davidson M, et al. Effect of combined risedronate and hormone replacement therapies on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 1890-1897.

102. Ettinger B, Pressman A, Schein J. Clinic visits and hospital admissions for care of acidrelated upper gastrointestinal disorders in women using alendronate for osteoporosis. Am J Manag Care 1998; 4: 1377-1382.

103. Faulkner DL, Lucy LM, Heath H, Minshall ME, Muchmore DB. A claims data assessment of patient compliance with alendronate (abstract). Osteoporos Int 1998; 8(Suppl 3): 21.

104. Yood RA, Emani S, Reed JI, Lewis BE, Charpentier M, Lydick E. Compliance with pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2003; 14: 965-968.

105. MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. Hormone replacement therapy use over a decade in an Australian population. Climacteric 2002; 5: 351-356.

106. Steel SA, Albertazzi P, Howarth EM, Purdie DW. Factors affecting long-term adherence to hormone replacment therapy after screening for osteoporosis. Climacteric 2003; 6: 96-103.

107. Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer JP, et al. Ten years’ experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. New Engl J Med 2004; 350: 1189-1199.

108. Fleisch H. Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action and clinical use in osteoporosis: an update. Horm Metab Res 1997; 29: 145-150.

109. Stock JL, Bell NH, Chesnut CH, III., et al. Increments in bone mineral density of the lumbar spine and hip and suppression of bone turnover are maintained after discontinuation of alendronate in postmenopausal women. Am J Med 1997; 103: 291-297.

110. Bjarnason NH, Delmas PD, Mitlak BH, et al. Raloxifene maintains favourable effects on bone mineral density, bone turnover and serum lipids without endometrial stimulation in postmenopausal women. 3-Year study results (abstract). Osteoporos Int 1998; 8(Suppl 3): 11.

111. Neele SJ, Evertz R, De Valk-De Roo GW, Roos JC, Netelenbos JC. Effect of 1 year of discontinuation of raloxifene or estrogen therapy on bone mineral density after 5 years of treatment in healthy postmenopausal women. Bone 2002; 30: 599-603.

112. Greenspan SL, Emkey RD, Bone HG, et al. Significant differential effects of alendronate, estrogen, or combination therapy on the rate of bone loss after discontinuation of treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137: 875-883.

113. Tonino RP, Meunier PJ, Emkey R, et al. Skeletal benefits of alendronate: 7-year treatment of postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 3109-3115.

114. Bagger YZ, Tanko LB, Alexandersen P, Ravn P, Christiansen C. Alendronate has a residual effect on bone mass in postmenopausal Danish women up to 7 years after treatment withdrawal. Bone 2003; 33: 301-307.

115. Orr-Walker B, Wattie DJ, Evans MC, Reid IR. Effects of prolonged bisphosphonate therapy and its discontinuation on bone mineral density in post-menopausal osteoporosis. Clin Endocrinol 1997; 46: 87-92.

116. Reid IR, Brown JP, Burckhardt P, et al. Intravenous zoledronic acid in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. New Eng J Med 2002; 346: 653-661.

117. Draper MW, Flowers DE, Huster WJ, Neild JA, Harper KD, Arnaud C. A controlled trial of raloxifene (LY139481) HCl: impact on bone turnover and serum lipid profile in healthy postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 1996; 11: 835-842.

118. Boss SM, Huster WJ, Neild JA, Glant MD, Eisenhut CC, Draper MW. Effects of raloxifene hydrochloride on the endometrium of postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177: 1458-1464.

119. Heaney RP, Draper MW. Raloxifene and estrogen: comparative bone-remodeling kinetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 3425- 3429.

120. Meunier PJ, Vignot E, Garnero P, et al. Treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or low bone density with raloxifene. Raloxifene Study Group. Osteoporos Int 1999; 10: 330-336.

121. Bjarnason NH, Sarkar S, Duong T, Mitlak B, Delmas PD, Christiansen C. Six and twelve month changes in bone turnover are related to reduction in vertebral fracture risk during 3 years of raloxifene treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int 2001; 12: 922-930.

122. Sambrook PN, Geusens P, Ribot C, et al. Alendronate produces greater effects tan raloxifene on bone density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone density: results of EFFECT (EFficacy of FOSAMAX® versus EVISTA® Comparison Trial) International. J Int Med 2004; 255: 503-511.

123. Delmas PD, Ensrud KE, Adachi JD, et al. Efficacy of raloxifene on vertebral fracture risk reduction in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: four-year results from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 3609-3617.

124. Ross LA, Alder EM. Tibolone and climacteric symptoms. Maturitas 1995; 21: 127-36. 125. Bjarnason NH, Bjarnason K, Haarbo J,Rosenquist C, Christiansen C. Tibolone: prevention of bone loss in late postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81: 2419-2422.

126. Ginsburg J, Prelevic G, Butler D, Okolo S. Clinical experience with tibolone (Livial) over 8 years. Maturitas 1995; 21: 71-76.

127. Tang B, Markiewicz L, Kloosterboer HJ, Gurpide E. Human endometrial 3 betahydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase can locally reduce intrinsic estrogenic/progestagenic activity ratios of a steroidal drug (Org OD 14). J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1993; 45: 345-351.

128. Lippuner K, Haenggi W, Birkhaeuser MH, Casez J-P, Jaeger P. Prevention of postmenopausal bone loss using tibolone or conventional peroral or transdermal hormone replacement therapy with 17b-estradiol and dihydrogesterone. J Bone Miner Res 1997; 12: 806-812.

129. Thiébaud D, Bigler JM, Renteria S, et al. A 3- year study of prevention of postmenopausal bone loss: conjugated equine estrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate versus tibolone. Climacteric 1998; 1: 202-210.

130. Rymer J, Chapman MG, Fogelman I, Wilson POG. A study of the effect of tibolone on the vagina in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 1994; 18: 127-133.

131. Nathorst-Böös J, Hammar M. Effect on sexual life — a comparison between tibolone and a continuous estradiol-norethisterone acetate regimen. Maturitas 1997; 26: 15-20.

132. Hammar M, Christau S, Nathorst-Böös J, Rud T, Garre K. A double-blind, randomised trial comparing the effects of tibolone and continuous combined hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with menopausal symptoms. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105: 904-911.

133. Farish E, Barnes JF, Rolton HA, Spowart K, Fletcher CD, Hart DM. Effects of tibolone on lipoprotein(a) and HDL subfractions. Maturitas 1994; 20: 215-219.

134. Parkin DE, Smith D, Al Azzawi F, Lindsay R, Hart DM. Effects of long-term ORG OD 14 administration on blood coagulation in climacteric wsomen. Maturitas 1987; 9: 95-101.

135. Bjarnason NH, Bjarnason K, Haarbo J, Coelingh Bennink HJT, Christiansen C. Tibolone: influence on markers of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 1752-1756.

136. Lloyd GWL, Patel NR, McGing EA, Cooper AF, Kamalvand K, Jackson G. Acute effects of hormone replacement with tibolone on myocardial ischaemia in women with angina. Int J Clin Pract 1998; 52: 155-157.

137. Cagnacci A, Mallus E, Tuveri F, Cirillo R, Setteneri AM, Melis GB. Effects of tibolone on glucose and lipid metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 251-253.

138. Prelevic GM, Beljic T, Balint-Peric L, Ginsburg J. Metabolic effects of tibolone in postmenopausal women with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Maturitas 1998; 28: 271-276.

139. Feher MD, Cox A, Levy A, Mayne P, LantAF. Short term blood pressure and metabolic effects of tibolone in postmenopausal women with non-insulin dependent diabetes. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996; 103: 281-283.

140. MacIntyre I, Stevenson JC, Whitehead MI, Wimalawansa SJ, Banks LM, Healy MJ. Calcitonin for prevention of postmenopausal bone loss. Lancet 1988; i: 900.

141. Fioretti P, Gambacciani M, Taponeco F, Melis GB, Capelli N, Spinetti. Effects of continuous and cyclic nasal calcitonin administration in ovariectomized women. Maturitas 1992; 15: 225-232.

142. Chesnut CH, III., Silverman S, Andriano K, et al. A randomized trial of nasal spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis: the prevent recurrence of osteoporotic fractures study. PROOF Study Group. Am J Med 2000; 109: 267-276.

143. Delmas PD, Bjarnason NH, Mitlak BH, et al. Effects of raloxifene on bone mineral density, serum cholesterol concentrations, and uterine endometrium in postmenopausal women. New Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1641-1647.

144. Studd J, Arnala I, Kicovic PM, Zamblera D, Kröger H, Holland N. A randomized study of tibolone on bone mineral density in osteoporotic postmenopausal women with previous fractures. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 92: 574-579.

145. Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene. Results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 282: 637-645.

146. Hillard TC, Whicroft SJ, Marsh MS, et al. Longterm effects of transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy on postmenopausal bone loss. Osteoporos Int 1994; 4: 341-348.

147. Komulainen M, Kroger H, Tuppurainen MT, Heikkinen AM, Honkanen RJ, Saarikoski S. Identification of early postmenopausal women with no bone response to HRT: results of a five-year clinical trial. Osteoporos Int 2000; 11: 211-218.

148. Gavaler JS. Thoughts on individualizing hormone replacement therapy based on the postmenopausal health disparities study data. J Women’s Health 2003; 12: 757-768.

149. Kraemer GR, Kraemer RR, Ogden BW, Kilpatrick RE, Gimpel TL, Castracane VD. Variability of serum estrogens among postmenopausal women treated with the same transdermal estrogen therapy and the effect on androgens and sex hormone binding globulin. Fertil Steril 2003; 79: 534-542.

150. Notelovitz M. Estrogen therapy in management of problems associated with urogenital aging: a simple diagnostic test and the effect of the route of hormone administration. Maturitas 1995; 22(Suppl): S31-S33.

151. Roy S, Caillouette JC, Roy T, Faden JS. Vaginal pH is similar to FSH for menopause diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190: 1272-1277.