Miastenia gravis en embarazo

Aproximadamente un 33% de las mujeres embarazadas con MG, pueden tener exacerbaciones de la miastenia. Puede ocurrir en el embarazo o en el posparto. Se recomiendan las siguientes guías para la conducción de tal eventualidad: l. Evitar el uso de sulfato de magnesia en una madre preeclámtica. 2. No usar por vía intravenosa un inhibidor de la colinesterasa porque puede ocurrir un parto prematuro. 3. Se puede usar el inhibidor por vía oral y, si es necesario, agregar prednisolona. 4. Las drogras inmunosupresoras están contraindicadas y se deben interrumpir, si se están administrando. 5. El parto por vía vaginal o por cesárea, se recomienda con anestesia epidural. 6. El recién nacido debe ser vigilado asiduamente en su respiración.

Crisis miasténicas

la crisis en MG, se define como el súbito empeoramiento de los síntomas, los cuales necesitan asistencia respiratoria. Las crisis surgen generalmente por infección (pulmonar), intervención quirúrgica, en la iniciación de altas dosis de prednisana en el tratamiento o por dosis excesivas de inhibidores de la colinesterasa.

Durante la crisis, se deben seguir las siguientes etapas: l. Asegurar la vía aérea y monitorizar los signos vitales. 2. Medir la función respiratoria, la capacidad vital y los gases arteriales. 3. Descontinuar los inhibidores de la colinesterasao 4. Transferir el paciente a la unidad de cuidados intensivos. 5. Organizar una plasmaféresis, si está disponible, o considerar una terapia con globulina inmune intravenosa. 6. Investigar la causa subyacente y tratarla vigorosamente. Se puede agregar predinisona y drogas inmunosupresoras.

Miastenida gravis en la edad avanzada

Los pacientes con MG después de los 60 años, son tratados primariamente con inhibidores de la colinesterasa. En las formas más severas, se les somete a prednisolona y azatioprina. la timectomía está indicada cuando hay timoma.

Inmunoterapia específica: El futuro del tratamiento

En forma ideal, la meta de la terapia en la miastenia gravis debe ser eliminar la respuesta autoinmune específica de los receptores de acetilcolina, sin interferir con el sistema inmune. Dados los actuales conocimientos de la enfermedad, debe ser posible diseñar una terapia inmune racional y específica.

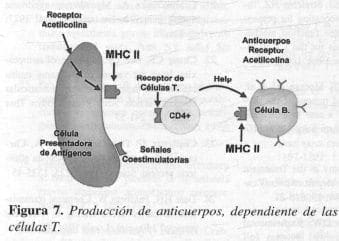

Primero, se sabe que las patogénesis de la MG, depende de un mecanismo mediado por anticuerpos. El tratamiento efectivo debe inhibir los anticuerpos contra los receptores de acetilcolina. Segundo, los anticuerpos que responden contra los receptores de acetilcolina son dependientes de las células T. Tercero, el receptor de acetilcolina es un antígeno altamente inmunogénico. La supresión de la respuesta al receptor, puede requerir métodos más poderosos que para otros antígenos menos potentes. Cuarto, la respuesta inmune a los receptores de acetilcolina son altamente heterogéneos. Las estrategias terapéuticas deben tener en cuenta el amplio espectro de la especificidad tanto de las células T, como de las células B.

Acceso directo a las células B

Ya que las células B producen anticuerpos patogénicos en la miasfenia gravis, parece lógico intentar interrumpir el proceso de la enfermedad en esta etapa crucial. Como se ha discutido antes, las células B y los anticuerpos que ellas producen, son altamente heterogéneos. Los anticuerpos producidos por ellas, son capaces de unirse a una amplia varidad de epitomes de los receptores de acetilcolina. Estos anticuerpos actúan como la “dirección” de cada célula B (Figura 7). Si las moléculas del receptor de acetilcolina están armadas con “cargas” letales, las células B pertinentes tomarán el antígeno letal y morirán, en una estrategia llamada “antígeno caliente suicida”. Experimentalmente, inmunotoxinas compuestas de receptores de acetilcolina unidos a la cadena A tóxica de ricino y al yodo 125, han sido usados exitosamente en animales (no inmunizados) o in vitro (50, 89). En la miastenia gravis, sin embargo, precisamente los mismos anticuerpos que sirven de dirección de las células B, están presentes en la circulación. Ellos pueden unir las moléculas inmunotóxicas, formando complejos que pueden precipitarse en el pulmón, hígado, riñones, sin nunca alcanzar su meta, pero con el riesgo de dañar estos órganos.

Este problema podría aplicarse virtualmente a cualquier estrategia diseñada para las células B específicas de los receptores de acetilcolina.

El antígeno al presentarse a las células, éstas lo intemalizan (el receptor de acetilcolina), lo procesan y después lo presentan los péptidos procesados en asociación con el complejo mayor de histocompatibilidad (MHC) clase 11como una molécula unida al sujeto. Las células T, recept.oras de antígeno específico de las células T ayudadoras (CD4+) se unen al complejo específico de péptidos MHC. La interacción del antígeno presentado a las células y la célula T, requiere señales coestimulatorias y es ayudado por adhesión de moléculas y citoquinas, lo cual resulta en estimul~ción de las células T. Estas activadas, ayudan a las células B específicas de los receptores de acetilcolina, que unen el antígeno (receptor de acetilcolina) a la superficie de los anticuerpos procesándolos y presentando el complejo MHC – péptido, como otras células presentadoras de antígenos. Ellos, por lo tanto interactúan con las células T uniéndose a los receptores de las células T; éstas prestan ayuda a las células B, por medio de moléculas de superficie y citoquinas (no ‘Postradas), con la resultante en proliferación de células B y la secreción de anticuerpos específicos contra los receptores de acetilcolina.

Acceso directo de las células

Como ya se ha anotado, las células T tienen una función de privote en la respuesta autoinmune de anticuerpos en la miastenia gravis (Figura 7) y tienen ciertas características que son susceptibles de accesos terapéuticos. Los receptores de las células T reconocen epitomes linares (asociados con MHC clase 11) que generalmente difieren de los epítomes determinados que se ajustan al reconocimiento por las células B (11). Esto permite marcar la importancia de las células T a través de sus receptores, mientras se reduce la posibilidad de intercepción por anticuerpos circulantes. Sin embargo, varios otros marcadores de superficie pueden servir como directores semiespecíficos para ser blanco. Las células T como objetivo pueden ser inactivadas o suprimidas por métodos que actual~ente están siendo probados.

Un método terapéutico no antígeno específico, incluye la reducción de las células T ayudadoras por medio de anticuerpos contra la molécula de superficia ayudadora (CD4) (14). El tratamiento con anticuerpos anti CD4, interfiere con las células T ayudadoras, produciendo un efecto inmunosupresivo general que ha sido usado experimentalmente para tratar miastenia gravis en animales.

La estrategia semiselectiva dirigida a las células T activadas, está siendo también explorada. Las células T incluidas en una respuesta inmune activa, expresan receptores para interleuquina 2, mientrs que las células T de memoria y en reposo, no (92). Una toxina interleuquina 2 para inmunoterapia, ha sido producida mediante ingeniería genética, y consiste en un receptor unido a media molécula de interleuquina 2 y al fragmento letal de la toxina diftérica. Este compuesto es aceptado por las células T activadas, que expresan receptores de interleuquina 2, lo cual produce su muerte. Experimentalmente se ha demostrado que esta toxina inhibe la proliferación de las células T específicas de los receptores de acetilcolina, así como también la producción de anticuerpos antirreceptores de acetilcolina.

Otro acceso terapéutico que recluta el sistema inmune del sujeto, tiene en cuenta la administración oral de antígenos. Aunque esta ingesta oral de antígeno es conocida desde tiempo para inducir tolerancia, este médoto tiene un renovado interés muy atractivo para el tratamiento de las enfermedaes autoinmunes (92). La administración oral de receptores de acetilcolina purificados, se ha observado que previene tanto el aspecto clínico como el inmunológico de la miastenia gravis en ratas modelos (99). Los efectos en la enfermedad de los humanos, están siendo sometidos a prueba.

Abstract

Over the past 15 years there has been much progress on the knowledge about the pathogenesis, immunology, and molecular biology of myasthenia gravis (MG. Diagnostic and clinical management methods are well defined and, in general, they are successful from the symptomatic viewpoint. But in spite of such advances, we remain ignorant about the mechanism that triggers the immune response in MG and although there are varied therapeutic approaches, the disease still is incurable.

Measurement of anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies is the most reliable and specific diagnostic method, closely followed by electromyography.

Most patients with MG require prednisone and immunosuppressor drugs. Thymr-:ctomy is commonly recommended for patients with generalized MG or thymoma. Plasmapheresis and immune globulin are indicated during episodes of exacerbation of the disease. Future treatment options are sought in the complex field of clinical immunology.

Referencias

1. Abramsky O, Aharonov A, Webb C, Fuchs s: Cellular immune response to acetylcholine receptor rich fraction, in patients with myastenia gravis. Clin Exp Inmunol 1975; 19:11-6

2. Adler H: Thymus und myasthenie. Arch Klin Chir 1937; 189:529-33

3. Albers JW, Hodach RJ, Kimmel DW et al: Penicillamine induced myasthenia gravis. Neurology 1980; 30: 1246-050

4. Almon Rr, Adrew AG, Appel SH: Serum globulin in myasthenia gravis. Inhibition of L-Bungaraton to acetylcholine receptors. Science 1974; 186: 55-71

5. Akakura Y: Mediastinoscopy. In: XI International Congress of Bronchoesophagology. Hakne, Japan 1965; 6

6. Aokit, Draghman DB, Asher DM, Gibbs CJ Jr, Bahmanyar S, Wolinsky JS: Attempts to implicate viruses in myasthenia gravis. Neurology 1985; 35: 185-92

7. Arsura E: Experience with intravenous immunoglobulin in myasthenia gravis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol1989; 53: suppl S; 170-9

8. Askanas V, Mc Ferrin J, Park-Matsumoto C, Lee CS, Engel WK: glucocorticoid increases acety lcholine estearase and organization of postsynaptic membrane in innervated cultured human muscle. Exp Neurol 1992; 15: 368-75

9. Behan PO, Currie S: Myastenia gravis. In: Clinical Neuroimmunology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Ca; 1978; 130-1

10. Bell ET: Tumors of the thymus in myasthenia gravis. Nervous Mental Dis 1917; 45: 30-43

11. Berzofsky JA, Brrett SJ, Streicher HZ, Takahashi H: Antigen processing for presentation to Thymophocytes: function, mechanisms, and implications for the T Cell receptoire. Immunol Rev 1988; 106: 5-31

12. Blalock A, Masan MF, Morgan HJ et al: Myasthenia gravis and tumors of the thymic region. Report of a case in which the tumor was removed. Ann Surg 1939; 110: 544-59

13. Blalock A: Thymectomy in the Treatment of myasthemia gravis. Report of twenty cases. J Thorac Surg 1944; 13: 316-21

14. Brostoff SW, Masan DW: Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: Success full treatment in vivo with a monoclonal antibody that recognizes T-helper cells. J Immuno11984; 133: 1938-42

15. Bucknall RD: Myasthenia associated with D-penicillamine therapy in rheumatois arthritis. Proc R Soc Med 1955; 23: 115-64

16. Buzzard EF: The clinical history and postmortem examination of five cases of myasthenia gravis. Brain 1905; 28: 438-83

17. Carlens E: Mediastinoscopy: A method for inspection and tissue biopsy in the superior mediastinum. Dis Chest 1959; 36: 343-8

18. CarIen E: Thymectomy far myasthenia gravis with the aid of mediastinoscopy. Opuscula Med 1968; 13: 175-9

19. Clagett OT, Eaton LM: Surgical treatment of myastenia gravis. J Thorac Surg 1947; 16: 62-6

20. Crile G Jr: Thymectomy through the neck. Surgery 1966; 59: 213-7

21. Czlonkowska A: Myasthemic syndrome during penicillamine tratment BMJ 1977; 2: 226-7

22. Chang CE, Lee Cy: Isolation of neuroloxins from the venom of Bungarus multicinctus and their modes of neuromuscular blocking action. Arch Pharmacodyn Ther 1962; 144: 241-57

23. Changeux JP, Debillers – Thiery A, Chemouilli P: Acetylcholine receptor; an allosteric protein. Science 1984; 225: 1335-45

24. Date HH, Feldberg W: Chemical transmission al motor nerve ending in voluntary muscle? J Physiol (Lond) 1934; 81: 39-40

25. Daroff RB: The office Tensilon test for ocular myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol 1986; 43: 843-4

26. Davies SE, Macartiney JC, Camplejohn RS et al: DNA flow cytometry of lhymomas. Histopathology 1989; 15: 77-83

27. Desmedt JE: Nature of the defecl of neuromuscular transmission in myasthenic patients posstetonic exhaustion. Nature 1957; 179: 156-7

28. De Robertis EDP, Bennett HS: Sorne features of submicroscopic morphology of synapses in frog and earthwarm. J Biophys Biochem Cyto11955; 1: 47-58

29. Eaton LM, Clagett OT: Presehnt stale of thymectomy in treatment of myasthenia gravis. Am J Med 1955; 19: 703-7

30. Edgewarth HA: A repart of progress on lhe use of ephedrine in a case of myasthenia gravis. JAMA 1930; 94: 1136-9

31. Elmqvist D: Neuromuscular transmission with special reference to myasthenia gravis. Acta Physiol Scand 1965; 64 suppl: 249

32. Elmqvist D, Hofmann WW, Kugelberg J, Qastel DMJ: An electrophysiological investigation of neuromuscular transmission in myasthenia gravis. J Physiol (Lond) 1964; 174: 417-34

33. Engel AG, Sahashi K, Lambert EH, Howard FM: The ultraestructural localization of the acetylcholine receptor, immunoglobulin G and the third and ninth complement components at the motor endplate and their implications for the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis. In: Aguayo AJ, Karpati G (eds). Current topics in nerve and muscle research. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica 1979; 111-22

34. Engel AG, Tsujihata M, Lindstrom JM, Lennon VA: the motor end plate in myasthenia gravis and in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis: a quantitative ultraestructural study. Ann NY Acad Sci 1976; 274: 60-79

35. Erb W: Zur casnistik der bulbaren lahmungen III Ueber einen Schimbar bulbarparalychisten symptomen complex mit bethiligung der extremitaten. Dtsch Z Nerv 1893; 4: 312-52

36. Fambrough GM, Frachman DB, Satymarti S: Neuromuscular junction in myasthenia gravis: decreased acetylcholine receptor. Science 1973; 182: 193-5

37. Flanagan WM, Corthesy F, Bram RJ, Crabtree GR: Nuclear association of a T-cell transcription factor blocked by FK-506 and cyclosporinA. Nature 1991; 352: 803-7

38. Galanaud P, Crevon MC, Erard D, Wallon C, Dormont J: Two processes for B-Cell triggering by T-independent antigene as evidenced

39. Goldflam S: Ueber einen scheimbar bu Ibaparalychisten symptomen complex mit betheilingung der extremitaten. Dtsch Z nerv 1893; 4: 312-52

40. Grandhomme F: Ueber Tumoren des Vorderen Mediastinumus und ihre Beziehungen zu der thumusdruse. Frankfurt am Main. Johannes alt. Verlasgsbuchhandlung 1900

41. Grob D, Arsura El, Brunner NG, Namba T: The course of myasthenia gravis and therapies affecting outcome. Ann NY Acad Sci 1987; 505: 472-99

42. Grob D, Brunner NG, Namba T: The natural course of myasthenia gravis and effect of therapeutic Measures. Ann NY Acad Sci 1981; 377: 652-69

43. Hamil P, Walker MB: the action of Prostigmin in neuromuscular disorders. J Physiol 1935; 82: 36-7

44. Hertel G, Mertens HG, Reuther P, Richer K: The treatment of myasthenia gravis with azathioprine. In: Day PC, ed Plasmapheresis and the immunobiology of myasthenia gravis. Boston: Hougthton Mifflin; 1979; 315-28

45. Hodlfeld R, Toyka KV; Michels M, Heiningerk, Conti – Tronconi B, Tzartos SJ: Acetylcholine receptor – specific human TLymphocyte lines. Ann NY Acad Sci 1987; 505: 27-38

46. Jolly F: Ueber myasthenia gravis pseudoparalytica. B erl Klin Wochenschr 1895; 31: 1-7

47. Keesey J, Buffkin D, Kebo D, Ho W, Hermann C Jr: Plasmaexchange alone as therapy for myasthenia gravis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1981; 377: 729-43

48. Kynes G: The results of thymectomy in myastheniagravis. BMJ 1949; 1: 611-6

49. Keynes g: Surgery ofthe thymus gland. Second (and third) thoughts. Lancet 1954;1: 1197-1202

50. Killen JA, Lindstrom JM: Specific Killing of Iymphocytes that cause experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis by ricin toxin -Acetylcholine receptor conjugates. J Immunol 1984; 133: 2549-53

51. Kirchner T, Hoppe F, Schalke B, Muller – Hermelink HK: Microenvironment of thymic myoid cells in myasthenia gravis. Virchow Arch (B) Cell Pathol 1988; 54: 295- 302

52. Kuks JBM, Oesterhuis HJGH, Limburg PC: The TH. Antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies decrease after thymectomy in patients with myasthenia gravis: Clinical correlation. J Autoimmun 1991; 4: 197-211

53. Laquer L, Weigert C: Beitrage zur Lehre von dem Erb’schem KranKheit 1. Uber die erb’schem Krankheit (Myasthenia gravis) (Iacquer) 2. Pathologisch- Anatomischer Beitrag zur Erb’schem krankheit (Myasthenia gravis) (Weiger). Neuro Zentralb 1901; 20: 594-601

54. Lee CY, Tseng LF: Distribution of Bungarus multicimctus venom following envenomation. Toxicology 1966; 3: 281-90

55. Lennon VA, Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME: Experimental antoimmune myasthenia gra- vis; cellular and humoral immune responses. Ann NY Acad Sci 1976; 274: 283-99

56. Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Whittingham S, Duane DD: Antibody to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis; prevalence, clinical correlates, and diagnostic valve. Neurology 1976; 26: 1054-9

57. Lindstrom JM, Lambert EH: Content of acetylcholine receptor and antibodies bound to receptor in myasthenia gravis, experimental autoimmune myastenia gravis and Eaton Lambert syndrome Neurology 1978, 28: 130-8

58. Link H, Olsson O, Sun J et al: Acetylcholine receptor-reactive T and B cells in myasthenia gravis and controls. J Clin Invest 1991; 87: 2191-5

59. Marino M, Muller-Hermelink HK: Thumoma and thymic carcinoma. Relation of thymoma epithelial cell to the cortical and medullary differentiation of the thymus. Virchows Arch IV (A) 1985; 407: 119-49

60. McFarlin DE, Barlow M, Strauss AJL: Antibodies to muscle and thymus in nonmyasthenic patients with thymoma: Clinical evaluation. N Engl J Med: 1966; 275: 1321-6

61. Mertens HG, Hertel G, Renther P et al: Effect not immunosuppressive drugs (azathioforine). Ann NY Acad Sci 1981; 377: 691-9

62. Miledi R, Molinoff P, Potter LT: Isolation of the cholinergic receptor protein of Torpedo electric tissue. Nature 1971; 229: 554-7

63. Miola L, Manfredi AA, Yuen MH, Howard JF Jr, Con ti-Tronco ni BM: T-helper epitomes on human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. Ann NY Acad

Sci 1993; 681: 196-218

64. Nastuk WL, Plascia OJ, Osserman KE: Changes in serum complement activity in patients with myasthenia gravis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1960; 105: 177-84

65. Noda M, Furatani H et al: Cloning and sequence analysis of calf cDNA and human genomic DNA encoding alfa-subunidad precursor of muscle acetylcholine receptor. Nature 1983; 305: 818-23

66. Nomori H, Horinouche H, Kaseda S et al: Evaluation of the malignant grade of thymoma by morphometric analysis. Cancer 1988; 6 1: 982-8

67. Norris EH: The Thymoma and thymic hyperplasia in myasthenia gravis with obser-vations on the general pathology. Am J Cancer 1936; 27: 421-33

68. Oppenheim H; Weiterer Beitrag zur Lehre von den acuten Nichteintrigen Encephalitis und der poliencephalumyelitis. Dtsch Nervenheikd 1899; 15; 1-27

69. Osserman KE; Myasthenia gravis in New York: Grune and Stratton, 1958; 79-86

70. Osserman KE, Kaplan Ll: Rapid diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis. JAMA 1952; 150: 265-8

71. Papatestas AE. GenKins G, Kornfeld P et al: Efects 01′ thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Ann Surg 1987; 206; 79-88

72. Patrick J, Lindstrom J: Autoimmune respose to acetylcholine receptor. Science 1973; 180; 871-2

73. Perlo VP, Amason B, Castleman B: The thymus gland in elderly patients with myasthenia gravis. Neurology 1975; 25: 294-5

74. Pestronk A, Drachman DB, Self SG; Measurement of juntional acetylcholine receptors in myasthenia gravis; Clinical correlates.Muscle Nerve 1985; 8: 245-51

75. Pinching AJ, Peters DK, Newson Davis J; Remission 01′ myasthenia gravis following plasma-exchange. Lancet 1976; 2: 1373-6

76. Ricci C, Rendina EA, Pesscarmona DE et al: Correlations Betwenn histological type, clinical behavioer and diagnosis in thymoma. Thorax 1989; 44: 455-60

77. Rosai J, Levine GD: Tumors 01′ the thymus. Atlas 01′ Tumors Pathology, second series, Fascicle 13. Bethesda, MD, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. 1976

78. Rowland LP: Myasthenia gravis. In; Matthews WB, Glaser GH, editors. Recent advances in clinical Neurology. Edinburgh: Livingstone 1978; 25-46

79. Safar D, Aimé C, Cohen-Kaminsky S et al: Antibodies to thumic epithelial cells in myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol 1991; 35; 101-10

80. Santa T, Engel AG, Lambert EH: Histometric study 01′ neuromuscular junction ultra structure. In: Myasthenia gravis. Neurology 1972; 22: 71-82

81. Schumacher CH, Roth P: Timektomie bei einem Fall von morbus Basedowi mit myasthenie. Mitteilungen, Grenzgebieten Med Chir 1912; 25: 746-65

82. Schumm F, Wietholter H, Fatch-Moghadam A, Dichgans J: Thymectomy in myasthenia gravis with pure ocular symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48: 332-7

83. Seybold ME, Howard FM Jr, Duane DD, Payne WS, Harricon EG Jr: Thymectomy in juvenile myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol 1971; 25: 385-92

84. Skrabanck P: Myastenia gravis: 300 years. J In Coll Phys Surg 1974; 3: 121-6

85. Simpson JA: Myasthenia gravis: A new hypothesis. Scott Med J 1960; 5: 419-36

86. Soffer LJ, Gravielove JL, Laqueur HP et al: The effects of anterior pituitary adenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in myasthenia gravis with tumor 01′ the thymus. J Mount Sinai Hosp 1948; 15: 73-82

87. Soffer LJ, Gravielove JL, Wolf BS: Effect 01′ ACTH on thymicmasses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1952; 12: 690-6

88. Stefansson K, Diepcrink ME, Richman DP, Gómez CM, Marton LS: Sharing 01′ antigenic determinauts between the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and proteins in Escherichia coli; Proteus vulgaris, and Klepsiella pneumoniae: possible role in the pathogenesis 01′ myastenia gravis. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 221-5

89. Sters RK, Biro G, Rahkik, Filipp G, Peper K: Experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis: can pretreatment with 125 I-labeled receptor prevent functional damage at the neuromuscular junction? J Immunol 1985; 134: 841-6

90. Strauss AJR, Seegal BC, Hus KC, Burkholder PM, Nastuk WL, Osserman KE: Immunotluorescence demostration 01′ a muscle binding, complement tixin serum globulin in myasthenia gravis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1960; 105: 184-91

91. Tan E, Hajinazarian M. Bay W, Netl J, Mendell JR: Acute renal failure resulting from intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Arch Neurolog 1993; 50: 137-9

92. Thompson HS, Staines NA: Could specific oral tolerancia be a therapy for autoimmune desease’) Immunol Today 1990; 11: 398-9

93. Tindall RSA: Humoral immunity in myasthenia gravis; effects 01′ steroids and thumectolllY. Neurology 1980; 30:554-7

94. Toyka KV, Drachman DB, Grit1in DE ct al: Myasthenia gravis: Study 01′ humoral immune mechanisms by passive transfer to mice. N Engl J Med 1977; 296: 125-31

95. Van Wilgenburg H: The effect ol’ prednisone on neuromuscular transmission in the rat diafragmo Eur Phannacol 1979; 55: 355-61

96. Viets HR: A historical review ol’ myasthenia gravis frolll 1672 to 1900. JAMA 1953; 153: 1273-80

97. Vincent A. Newsolll-Dais J: Acetylcholine receptor antibody as a diagnostic tcst for myasthenia gravis: results in 153 validates cases and 2967 diagnostic assays. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48: 1246-52

98. Walker MB: Treatment 01′ myasthenia gravis with physostigmine. Lancet 1934; 1: 1200-1

99. Wang ZY, Qiao J, Link H: Suppression 01′ experimental autoimmune myasthcnia gravis by oral administration of acetylcholine receptor. J Neuroimmulol 1993; 44: 209-14

100.Wick MR, Rosai J: Epithelial tumors. In: Givel JC, editor. Surgery 01′ the thYlllUS. Berlin: Srpinger Verlang 1990

10l.Willis T: De auima brutorum. Oxford, Theatro Sheldoniano. 1672. English translation in: Pordage S. (Trans). The London practice 01′ phy sick two discourses concerning de soul 01′ brutes.

102.Witzemann V, Barg B, Nishikawa Y, Sakmann B. Numa s: Dil’l’erential reglllation 01′ muscle acetylcholine receptor gama and eta-sllbllnit mRNAs. FEBS Lett 1987: 223: 104-12.

Correspondencia: Dr. Jaime De la Hoz. Carrera 15 No. 84-54 Cons. 30, Piso 4, Santafé de Bogotá, D. C.