Resultados

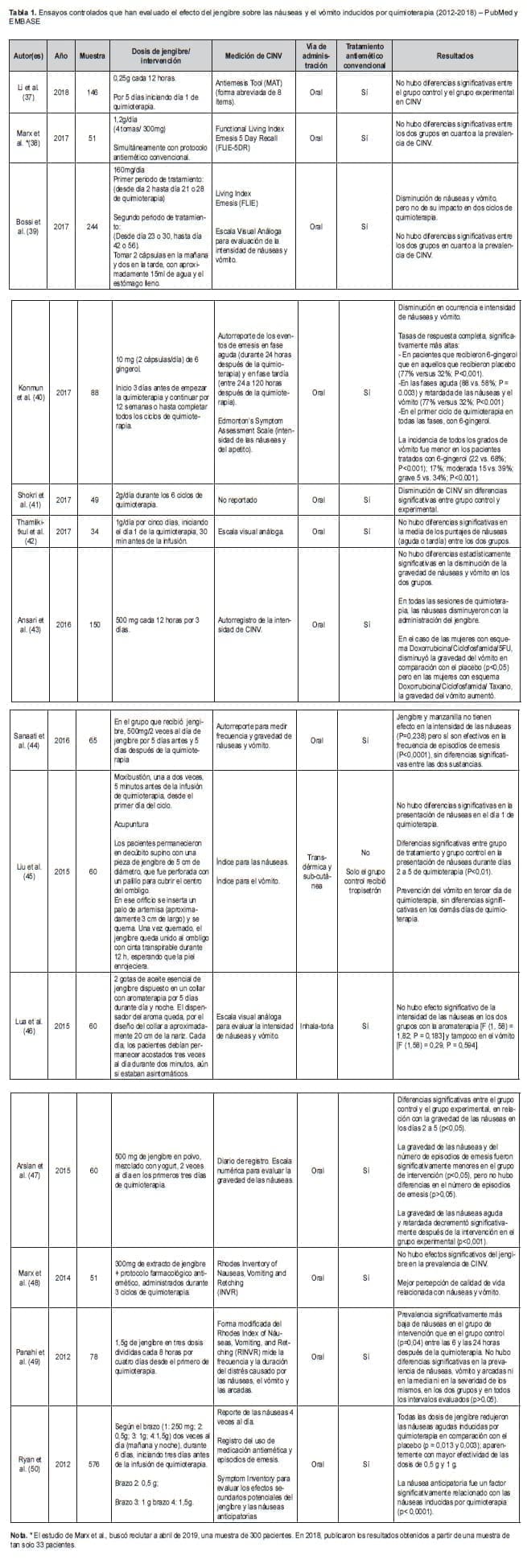

La Tabla 1 muestra una síntesis de los artículos seleccionados, enfatizando en la dosis de jengibre administrada, la vía de administración, el uso de tratamiento farmacológico antiemético, los instrumentos utilizados para medir las náuseas y el vómito, y los resultados en relación con la respuesta terapéutica.

Discusión y Conclusiones

Discusión y Conclusiones

Entre enero de 2012 y septiembre de 2018, se publicaron en las bases de datos EMBASE y PubMed, 14 ensayos clínicos controlados sobre el uso de jengibre para el control de CINV en pacientes oncológicos. Las publicaciones de estudios que utilizaron este diseño de investigación son escasas, con leve tendencia al aumento en 2018.

Desde octubre de 2017, Marx et al., desarrollan un estudio multicéntrico, aleatorizado doble ciego controlado con placebo con dos brazos paralelos y asignación 1: 1, basado en el protocolo SPICE (Supplemental Prophylactic Intervention for Chemotherapy Induced Nausea and Emesis). En este se administran 60 mg/día de jengibre, distribuidos en 4 cápsulas de 15mg para 4 tomas diarias regulares.

El estudio finalizó en abril-mayo de 2019. Si bien los resultados reportados en 2018 con base en 33 pacientes no son concluyentes, las expectativas de los investigadores están centradas en el prometedor efecto del suplemento de jengibre para mejorar CINV, así como la percepción de fatiga y el compromiso nutricional (51).

Motilidad intestinal disminuida

Los resultados de esta revisión demuestran que en tres estudios (40, 47, 50) (ver Tabla 1), hay alguna evidencia de la eficacia del jengibre para disminuir las náuseas y/o el vómito inducidos por quimioterapia, en diversos parámetros (frecuencia, intensidad, gravedad). Estos estudios respaldan la afirmación de Giacosa et al. (26) en relación con la eficacia del jengibre para el tratamiento de las náuseas, el vómito e incluso de la motilidad intestinal disminuida.

No obstante, once estudios muestran que esta sustancia no tuvo un efecto mayor que el tratamiento antiemético convencional sobre CINV. Incluso, en el estudio de Liu et al., en el cual no se administró tratamiento antiemético estándar de manera simultánea con la moxibustión y la acupuntura, las náuseas fueron las mismas entre los dos grupos en el día 1 de la quimioterapia (45).

Dos estudios reportaron que el jengibre parece actuar mejor sobre las náuseas (40, 43) que sobre la emesis (44, 47). Es pertinente tener presente la heterogeneidad de los pacientes incluidos en los estudios, así como de los esquemas de quimioterapia utilizados, que variaron desde levemente emetizantes hasta altamente emetizantes.

Con excepción del estudio de Liu et al., basado en los principios de la moxibustión y la acupuntura, procedimientos propios de la Medicina China, en ninguno de los estudios se administró el jengibre como única sustancia antiemética (45).

En trece de los catorce estudios, el jengibre se administró además del tratamiento farmacológico antiemético convencional, que se administra por protocolo a los pacientes que se encuentran en quimioterapia.

Sin embargo, la tendencia mostró que no hay diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre estos dos tratamientos en CINV.

En cuanto a las vías de administración, en 12 de los 14 estudios revisados, se utilizó la vía oral, con presentación en cápsulas o polvo. En un estudio se reportó el uso de aceite de Jengibre administrado en forma de aromaterapia (46) y en otro, la moxibustión y la acupuntura (45).

Infusiones herbales o té

En ninguno de los estudios revisados se reporta el uso de infusiones herbales o té. Probablemente, esto se deba a la necesidad de medir la dosis de una manera precisa, lo que en las preparaciones mencionadas resultaría francamente inviable. El uso del jengibre como remedio casero antiemético, típicamente administrado a través de infusiones, no tendría respaldo científico con base en esta revisión.

Los estudios revisados no coinciden aún en una dosis diaria específica o mínima de jengibre, para lograr el efecto antiemético; estas variaron entre 0,5 hasta 3,5 g (52), y en el caso de la aromaterapia, con dos gotas se esperaba obtener resultados terapéuticos. Esta limitación relacionada con la estabilidad química de las preparaciones con jengibre, ya había sido enunciada hace prácticamente dos décadas por Ernst y Pittler (53).

Con excepción de uno (45) de los 14 estudios revisados, en ningún otro se reportaron efectos colaterales con el uso del jengibre. Este hallazgo es coherente con la conclusión de Ali et al., según la cual el jengibre es una medicina herbal segura con pocos efectos adversos tras su administración (54).

Este es un dato relevante que amerita mayor investigación y análisis debido a que la inocuidad de su administración, podría representar una alternativa prometedora si se hallara un mayor efecto antiemético en esta sustancia.

El efecto antiemético del jengibre

En el estudio de Marx et al. (48) publicado recientemente y en el de Ryan et al. (50), el efecto antiemético del jengibre produjo una mayor percepción de calidad de vida entre los pacientes.

Y, además, en otro de los estudios (38) se encontró una menor percepción de astenia relacionada con el cáncer. Estos son hallazgos relevantes, en tanto el mayor desenlace que puede esperarse de una intervención en el contexto de la enfermedad crónica, es el bienestar subjetivo que se traduce en mejor calidad de vida.

De acuerdo con los resultados de los estudios revisados, la evidencia del efecto antiemético del jengibre (en uno o más de sus componentes) sobre CINV es insuficiente, con una tendencia a indicar que esta raíz tiene algún efecto antiemético que no supera al del tratamiento farmacológico convencional.

Se requiere de mayor investigación al respecto que permita determinar la dosificación del jengibre para que su acción sea antiemética en CINV y estudiar de manera rigurosa los efectos colaterales del mismo.

En conclusión, con base en la evidencia publicada entre 2012 y 2018, no es posible afirmar que el jengibre sea eficaz para controlar CINV.

Conflicto de interés

Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Consideraciones éticas

Los autores declaran, de acuerdo con los principios establecidos en la Declaración de Helsinki, el Reporte Belmont, las Pautas CIOMS, GPC/ICH y la Resolución 8430 de octubre 4 de 1993, que esta investigación se consideró “sin Riesgo”.

Referencias

- 1. Sánchez R, Venegas M. Aproximaciones complementarias y alternativas al cuidado de la salud en el

Instituto Nacional de Cancerología: estudio de prevalencia. Alternative and Complementary Medicine at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia: A Prevalence Survey (English). 2010; 14: 135-43. - 2. Anestin AS, Duouis G, Lanctôt D, Bali M. The Effects of the Bali Yoga Program for Breast Cancer Patients on Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: Results of a Partially Randomized and Blinded Controlled Trial. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017.

- 3. Satija A, Bhatnagar S. Complementary Therapies for Symptom Management in Cancer Patients. Indian Journal of Palliative Care. 2017; 23(4): 468-79.

- 4. Frączek P, Kilian-Kita A, Püsküllüoglu M, Krzemieniecki K. Acupuncture as anticancer treatment? Contemporary Oncology. 2017(20):453 – 457.

- 5. Singletary K. Ginger. Nutrition Today. 2010; 45(4): 171– 83.

6. Sommariva S, Pongiglione B, Tarricone R. Impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on health-related quality of life and resource utilization: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Oncology / Hematology. 2016; 99: 13-36. - 7. Singh P, Yoon SS, Kuo B. Nausea: A Review of pathophysiology and therapeutics. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016; 9(1): 98-112.

- 8. Mukoyama N, Yoshimi A, Goto A, Kotani H, Miyazaki M, Noda Y, et al. An analysis of behavioral and genetic risk factors for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Japanese subjects. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2016; 39(11): 1852-8.

- 9. Stern R. The psychophysiology of nausea. Acta Biol Hung. 2002; 53: 589-99.

- 10. Gatzoulis MA, Standring S, Borley NR, Collins P, Crossman AR. Gray’s Anatomy: The anatomical basis of clinical practice. Edimburgo: Churchill Livingstone- Elsevier; 2008.

- 11. Miller AD, Leslie RA. The area postrema and vomiting. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1994; 15(4): 301.

Bibliografía

- 12. Kowalski A, Rapps N, Enck P. Functional cortical imaging of nausea and vomiting: A possible approach. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2006; 129: 28-35.

- 13. Farrell C, Brearley SG, Pilling M, Molassiotis A. The impact of chemotherapy-related nausea on patients’ nutritional status, psychological distress and quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013; 21(1): 59-66.

- 14. Dikken C, Wildman K. Control of nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2013; 12(8): 24.

- 15. Janicki PK. Management of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: role of netupitant–palonosetron combination. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2016(1): 693-699.

- 16. Tamura K, Aiba K, Saeki T, Nakanishi Y, Kamura T, Baba H, et al. Breakthrough chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: report of a nationwide survey by the CINV Study Group of Japan. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017; 22(2): 405-12.

- 17. Navari RM, Nagy CK, Gray SE. The use of olanzapine versus metoclopramide for the treatment of breakthrough chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2013; 21(6): 1655-63.

- 18. Stieler JM, Reichardt P, Riess H, Oettle H. Treatment Options for Chemotherapy-Induced Nauseas and Vomiting: Current and Future. American Journal of Cancer. 2003; 2(1): 15-26.

- 19. Spartinou A, Nyktari V, Papaioannou A. Granisetron: A review of pharmacokinetics and clinical experience in chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017; 13(12): 1289-97.

- 20. Adel N. Overview of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and evidence-based therapies. Am J Manag Care. 2017; 23(14): 259-65.

- 21. Jordan K, Jahn F, Aapro M. Recent developments in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a comprehensive review. Annals of Oncology. 2015; 26(6): 1081-90.

Fuentes

- 22. Viljoen E, Visser J, Koen N, Musekiwa A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy associated nausea and vomiting. Nutrition Journal. 2014; 13(1).

- 23. Koçak İ, Yücepur C, Gökler O. Is Ginger Effective in Reducing Post-Tonsillectomy Morbidity? A Prospective Randomised Clinical Trial. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2017.

- 24. Sontakke S, Thawani V, Naik MS. Ginger as an antiemetic in nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy: A randomized, cross over, double blind study. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 2003; 35(1): 32-6.

- 25. Hori Y, Miura T, Hirai Y, Fukumura M, Nemoto Y, Toriizuka K, et al. Pharmacognostic studies on ginger and related drugs—part 1: five sulfonated compounds from Zingiberis rhizome (Shokyo). Phytochemistry. 2003; 62: 613-617.

- 26. Giacosa A, Morazzoni P, Bombardelli E, Riva A, Porro GB, Rondanelli M. Can nausea and vomiting be treated with ginger extract? European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2015; 19(7): 1291-6.

- 27. Wampold BE, Frost ND, Yulish NE. (2016). Placebo Effects in Psychotherapy: A Flawed Concept and a Con-torted History. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2016; 3(2): 108–120

- 28. Wampold BE, Minami T, Tierney SC, Baskin TW, Bhati KS. The placebo is powerful: Estimating placebo effects in medicine and psychotherapy from randomized clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005; 61(7): 835- 54.

- 29. Haug M. Explaining the placebo effect: Aliefs, beliefs, and conditioning. Philosophical Psychology. 2011; 24(5): 679-98.

- 30. Kirsch I. Placebos Handbook of Psychology – Health and Medicine. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

- 31. Beecher HK. The powerfull placebo. JAMA. 1955; 159(17): 1602 – 6.

- 32. Kienle GS, Kiene H. The powerful placebo effect: Fact or fiction? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997; 50(12): 1311-8.

Referencias Bibliográficas

- 33. Darragh M, Booth RJ, Consedine NS. Who responds to placebos? Considering the “placebo personality” via a transactional model. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2015; 20(3): 287-95.

- 34. Hall KT, Lembo AJ, Kirsch I, Ziogas DC, Douaiher J, Jensen KB, et al. Catechol-O-Methyltransferase val158met Polymorphism Predicts Placebo Effect in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7(10): 1-6.

- 35. Dodd S, Dean OM, Vian J, Berk M. Review: A Review of the Theoretical and Biological Understanding of the Nocebo and Placebo Phenomena. Clinical Therapeutics. 2017; 39: 469-76.

- 36. Meyer B, Yuen KSL, Büchel C, Kalisch R, Ertl M, Polomac N, et al. Neural mechanisms of placebo anxiolysis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015; 35(19): 7365-73.

- 37. Li X, Qin Y, Liu W, Zhou XY, Li YN, Wang LY. Efficacy of Ginger in Ameliorating Acute and Delayed Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Among Patients with Lung Cancer Receiving Cisplatin-Based Regimens: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2018; 17(3): 747-754. doi: 10.1177/1534735417753541.

- 38. Marx W, McCarthy A, Ried K, McKavanagh D, Vitetta L, Sali A, Lohning A, Isenring E. The Effect of a Standardized Ginger Extract on Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea- Related Quality of Life in Patients Undergoing Moderately or Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy: A Double Blind, Randomized, Placebo Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2017; 9: 867. doi:10.3390/nu9080867

- 39. Bossi P, Alfieri S, Granata R, Bergamini C, Cortinovis D, Bidoli P, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, multicenter study of a ginger extract in the management of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. Annals of Oncology. 2017; 28(10): 2547-51.

Fuentes Bibliográficas

- 40. Konmun J, Danwilai K, Ngamphaiboon N, Sookprasert A, Sripanidkulchai B, Subongkot S. A phase II randomized doubleblind placebo-controlled study of 6-gingerol as an anti-emetic in solid tumor patients receiving moderately to highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Medical Oncology. 2017; 34(4).

- 41. Shokri F, Gharebaghi PM, Esfahani A, Sayyah-Melli, M., Shobeiri MJ, et al. Comparison of the complications of platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy with and without ginger in a pilot study on ovarian cancer patients. International Journal of Women’s Health and Reproduction Sciences. 2017; 5(4): 324-31.

- 42. Thamlikitkul L, Srimuninnimit V, Akewanlop C, Ithimakin S, Techawathanawanna S, Korphaisarn K, et al. Efficacy of ginger for prophylaxis of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in breast cancer patients receiving adriamycin–cyclophosphamide regimen: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, crossover study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017; 25(2): 459-64.

- 43. Ansari M, Porouhan P, Omidvari S, Ahmadloo N, Nasrollahi H, Hamedi SH, et al. Efficacy of ginger in control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in breast cancer patients receiving doxorubicin based chemotherapy. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016; 17(8): 3875-8.

- 44. Sanaati F, Najafi S, Kashaninia Z, Sadeghi M. Effect of ginger and chamomile on nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy in Iranian women with breast cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016; 17(8): 4127-31.

- 45. Liu YQ, Sun S, Dong HJ, Zhai DX, Zhang DY, Shen W, et al. Wrist-ankle acupuncture and ginger moxibustion for preventing gastrointestinal reactions to chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2015; 21(9): 697-702.

- 46. Lua PL, Salihah N, Mazlan N. Effects of inhaled ginger aromatherapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2015; 23: 396-404.

Otras Referencias

- 47. Arslan M, Ozdemir L. Oral Intake of Ginger for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Among Women with Breast Cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015; 19(5): E92-E7.

- 48. Marx W, Isenring L, Ried K, Sali A, McCarthy AL, Vitetta L, et al. Can ginger ameliorate chemotherapy-induced nausea? Protocol of a randomized double blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014; 14.

- 49. Panahi Y, Saadat A, Sahebkar A, Hashemian F, Taghikhani M, Abolhasani E. Effect of ginger on acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A pilot, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2012; 11(3): 204-11.

- 50. Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, Hickok JT, Morrow GR, Dakhil SR, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: a URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012; 20(7): 1479-89.

- 51. Marx W, McCarthy A, Marshall S, Crichton M, Molassiotis A, Ried K, Bird R, Lohning A, Isenring E. Supplemental prophylactic intervention for chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis (SPICE) trial: Protocol for a multicentre double-blind placebo controlled randomised trial. Nutrition & Dietetics. 2018. DOI: 10.1111/1747- 0080.12446

- 52. Lee J, Oh H. Ginger as an Antiemetic Modality for Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013; 40(2): 163-70.

- 53. Ernst E, Pittler MH. Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2000; 84(3): 367-71.

- 54. Ali BH, Blunden G, Tanira MO, Nemmar A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): A review of recent research. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008. 46: 409–420.